This lesson was reported from:

A chapter of The United States: An Open Ended History, a free online textbook. Adapted in part from open sources.

For Your Consideration:

-

Describe the Sugar Act, the Quartering Act, and the Stamp Act. Why did these acts of Parliament so upset American colonists?

-

How did American colonists resist these acts?

-

What was the Boston Massacre? How did Paul Revere and other Sons of Liberty talk about this event?

-

What was the Boston Tea Party? How did Parliament respond to it?

-

What did it mean to call someone a patriot? A loyalist?

The Stamp Act and Other Laws

The French and Indian War (1754–63) was a watershed event in the political development of the colonies. Following Britain’s acquisition of French territory in North America, King George III issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763 limiting westward expansion of colonial settlements, all with the goal of organizing his newly enlarged North American empire and avoiding conflict with Native Americans beyond the Appalachian Mountains. This alienated colonists who had fought the war with the promise of a new source of free or cheap land in mind.

Furthermore, the French and Indian War nearly doubled Great Britain’s national debt, and Parliament was keen to find new sources of revenue to settle this debt.

In 1764, Parliament began allowing customs officers to search random houses in the colonies for smuggled goods on which no import tax had been paid. British authorities thought that if profits from smuggled goods could be directed towards Britain, the money could help pay off debts. Colonists were horrified that they could be searched without warrant at any given moment.

Also in 1764, Parliament began to impose new taxes on the colonists. The Sugar Act of 1764 reduced taxes on sugar and molasses imposed by the earlier Molasses Act, but at the same time strengthened the enforcement of tax collection, making smuggling harder. It also provided that British judges, and not colonial juries – who, as consumers of the smuggled sugar in question, might be more sympathetic to the accused – would try cases involving violations of that Act.

The next year, Parliament passed the Quartering Act, which required the colonies to provide room and board for British soldiers stationed in North America; the soldiers would serve various purposes, chiefly to enforce the previously passed acts of Parliament.

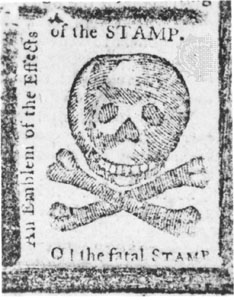

Following the Quartering Act, Parliament passed one of the most infamous pieces of legislation: the Stamp Act. Previously, Parliament imposed only external taxes on imports, paid by the merchants who actually brought goods into the colonies. The Stamp Act provided the first internal tax paid directly by the colonists when they purchased books, newspapers, pamphlets, legal documents, playing cards, and dice. These items – important for communication and entertainment – now required an official tax stamp as proof of payment.

The colonial legislature of Massachusetts requested a conference on the Stamp Act; the Stamp Act Congress met in October that year, petitioning the King and Parliament to repeal the act before it went into effect at the end of the month, crying “taxation without representation.” Specifically, these colonists argued that as English subjects, they were entitled to a voice in Parliament. As it stood, the colonists had no right to vote – so Parliament could impose all of the unpopular laws and taxes that it liked on colonists, and they faced no consequences at the ballot box… Without a member of Parliament working on their behalf, this was hardly the outcome of a democracy – it may as well be the act of an absolute tyrant.

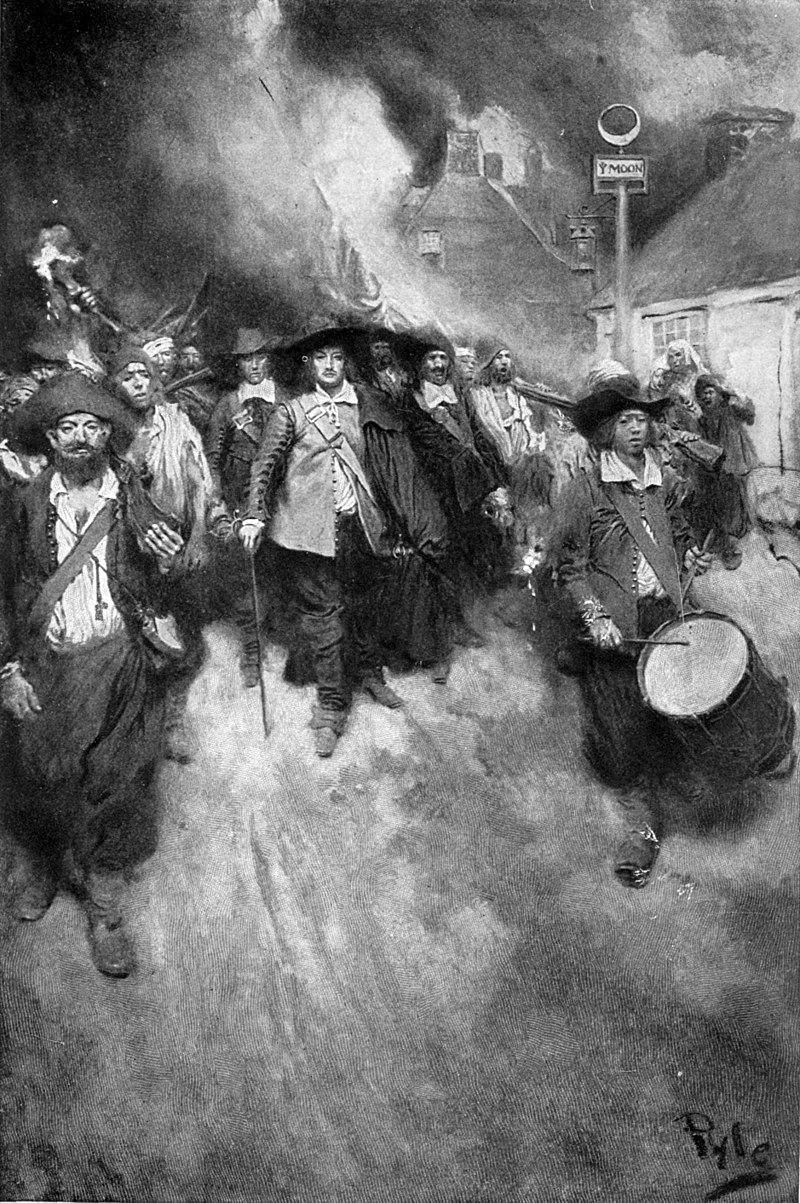

The Stamp Act faced vehement opposition throughout the colonies. Merchants and consumers alike threatened to boycott British products. Thousands of New Yorkers rioted near the location where the stamps were stored. In Boston, the Sons of Liberty, a violent group led by radical statesman Samuel Adams, destroyed the home of Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson. Adams wanted to free people from their awe of social and political superiors, make them aware of their own power and importance, and thus arouse them to action. Toward these objectives, he published articles in newspapers and made speeches in town meetings, instigating resolutions that appealed to the colonists’ democratic impulses.

The Sons of Liberty also popularized the use of tar and feathering to punish and humiliate offending government officials starting in 1767. This method was also used against those who threatened to break the boycott and later against British Loyalists during the American Revolution.

Parliament did indeed repeal the Stamp Act, but additionally passed the Declaratory Act, which stated that Great Britain retained the power to tax the colonists, even without representation.

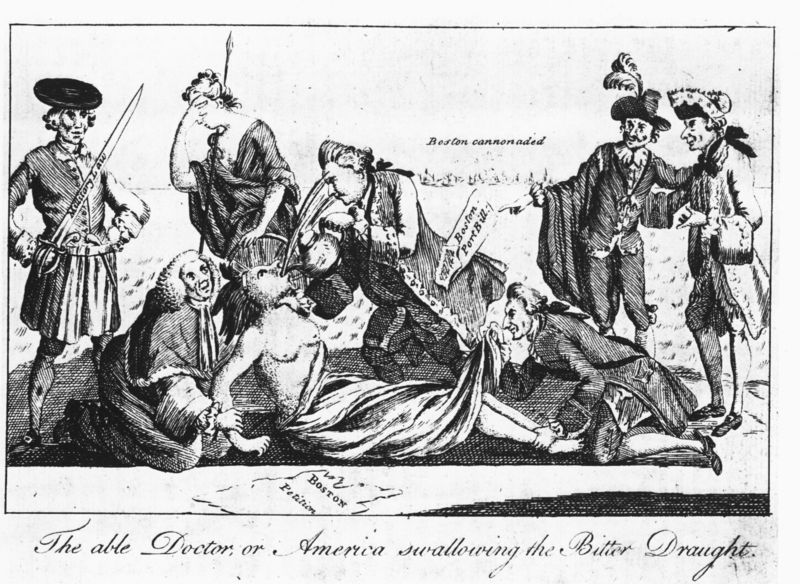

Believing that the colonists only objected to internal taxes, Chancellor of the Exchequer Charles Townshend proposed bills that would later become the Townshend Acts. The Acts, passed in 1767, taxed imports of tea, glass, paint, lead, and even paper. The colonial merchants again threatened to boycott the taxed products, reducing the profits of British merchants, who in turn petitioned Parliament to repeal the Townshend Acts. Parliament eventually agreed to repeal much of the Townshend legislation. But Parliament refused to remove the tax on tea, implying that the British retained the authority to tax the colonies despite a lack of representation.

In Boston, enforcement of the new regulations provoked violence. When customs officials sought to collect duties, they were set upon by the populace and roughly handled. For this infraction, two British regiments were dispatched to protect the customs commissioners, but the presence of British troops in Boston was a standing invitation to disorder.

On March 5, 1770, a large crowd gathered around a group of British soldiers. The crowd grew threatening, throwing snowballs, rocks, and debris at them. One soldier was clubbed and fell. There was no order to fire, but the soldiers fired into the crowd anyway. They hit 11 people; three civilians died at the scene of the shooting, and two died after the incident. Crispus Attucks was an American stevedore of African and Native American descent, widely regarded as the first person killed in the Boston that day and thus the first American killed in the American Revolution. Dubbed the “Boston Massacre,” the incident was framed as dramatic proof of British heartlessness and tyranny. Widespread – and biased – patriot propaganda such as Paul Revere’s famous print soon began to turn colonial sentiment against the British. This, in turn, began a downward spiral in the relationship between Britain and the Province of Massachusetts.

Beginning in 1772, Samuel Adams in Boston set about creating new Committees of Correspondence, which linked Patriots in all 13 colonies and eventually provided the framework for a rebel government. Virginia, the largest colony, set up its Committee of Correspondence in early 1773, on which Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson served.

A total of about 7000 to 8000 Patriots served on “Committees of Correspondence” at the colonial and local levels, comprising most of the leadership in their communities. Loyalists were excluded. The committees became the leaders of the American resistance to British actions, and largely determined the war effort at the state and local level. Later, when the First Continental Congress decided to boycott British products, the colonial and local Committees took charge, examining merchant records and publishing the names of merchants who attempted to defy the boycott by importing British goods.

In 1773, Parliament passed the Tea Act, which exempted the British East India Company from the Townshend taxes. Thus, the East India Company gained a great advantage over other companies when selling tea in the colonies – their tea was cheaper, and American smugglers faced the uncomfortable prospect of being undersold and put out of business entirely. A town meeting in Boston determined that the cheap British tea would not be landed, and ignored a demand from the governor to disperse. On December 16, 1773, a group of men, led by Samuel Adams, some dressed to evoke the appearance of American Indians, boarded the ships of the British East India Company and dumped £10,000 worth of tea from their holds (around a million dollars in modern terms) into Boston Harbor. Decades later, this event became known as the Boston Tea Party and remains a significant part of American patriotic lore.

Parliament responded by passing the Coercive Acts which came to be known by colonists as the Intolerable Acts. Intended as collective punishment to turn colonists against the Sons of Liberty and other radical patriots, they by and large had the opposite effect, further darkening colonial opinion towards the British. The Coercive Acts consisted of four laws. The first was the Massachusetts Government Act which altered the Massachusetts charter and restricted town meetings. The second act was the Administration of Justice Act which ordered that all British soldiers to be tried were to be arraigned in Britain, not in the colonies. The third Act was the Boston Port Act, which closed the port of Boston until the British had been compensated for the tea lost in the Boston Tea Party. The fourth Act was the Quartering Act of 1774, which allowed royal governors to house British troops in the homes of citizens without requiring permission of the owner.

In late 1774, the Patriots – as colonists who wished for independence came to be known – set up their own alternative government to better coordinate their resistance efforts against Great Britain; other colonists preferred to remain aligned to the Crown and were known as Loyalists. At the suggestion of the Virginia House of Burgesses, colonial representatives met in Philadelphia on September 5, 1774, “to consult upon the present unhappy state of the Colonies.” Delegates to this meeting, known as the First Continental Congress, were chosen by provincial congresses or popular conventions. Only Georgia failed to send a delegate; the total number of 55 was large enough for diversity of opinion, but small enough for genuine debate and effective action. The division of opinion in the colonies posed a genuine dilemma for the delegates. They would have to give an appearance of firm unanimity to induce the British government to make concessions. But they also would have to avoid any show of radicalism or spirit of independence that would alarm more moderate Americans.

A cautious keynote speech, followed by a “resolve” that no obedience was due the Coercive Acts, ended with adoption of a set of resolutions affirming the right of the colonists to “life, liberty, and property,” and the right of provincial legislatures to set “all cases of taxation and internal polity.”

The article was adapted in part from:

Slaves lived below the decks in conditions of squalor and indescribable horror. Disease spread and ill health was one of the biggest killers. Mortality rates were high, and death made conditions even worse. Many crew members avoided going into the hold because of the smell, the sights, and the sounds below deck. Even though the corpses were thrown overboard, living slaves might be shackled for hours and sometimes days to someone who was dead.

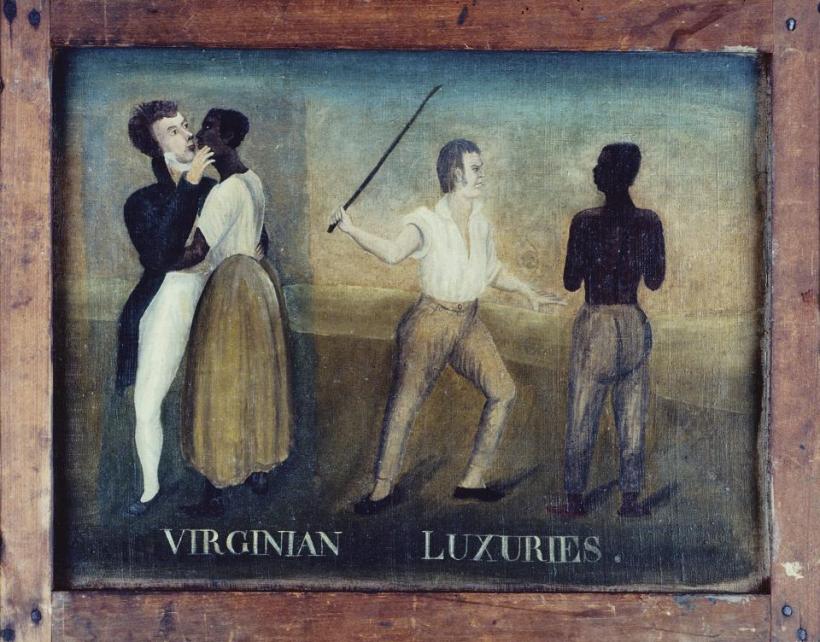

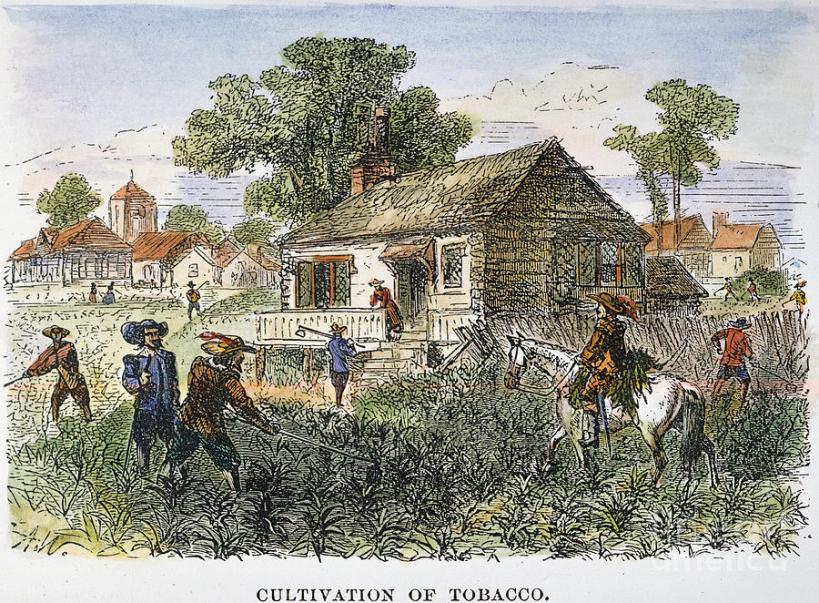

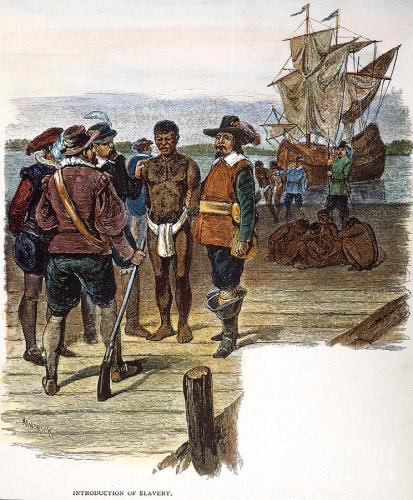

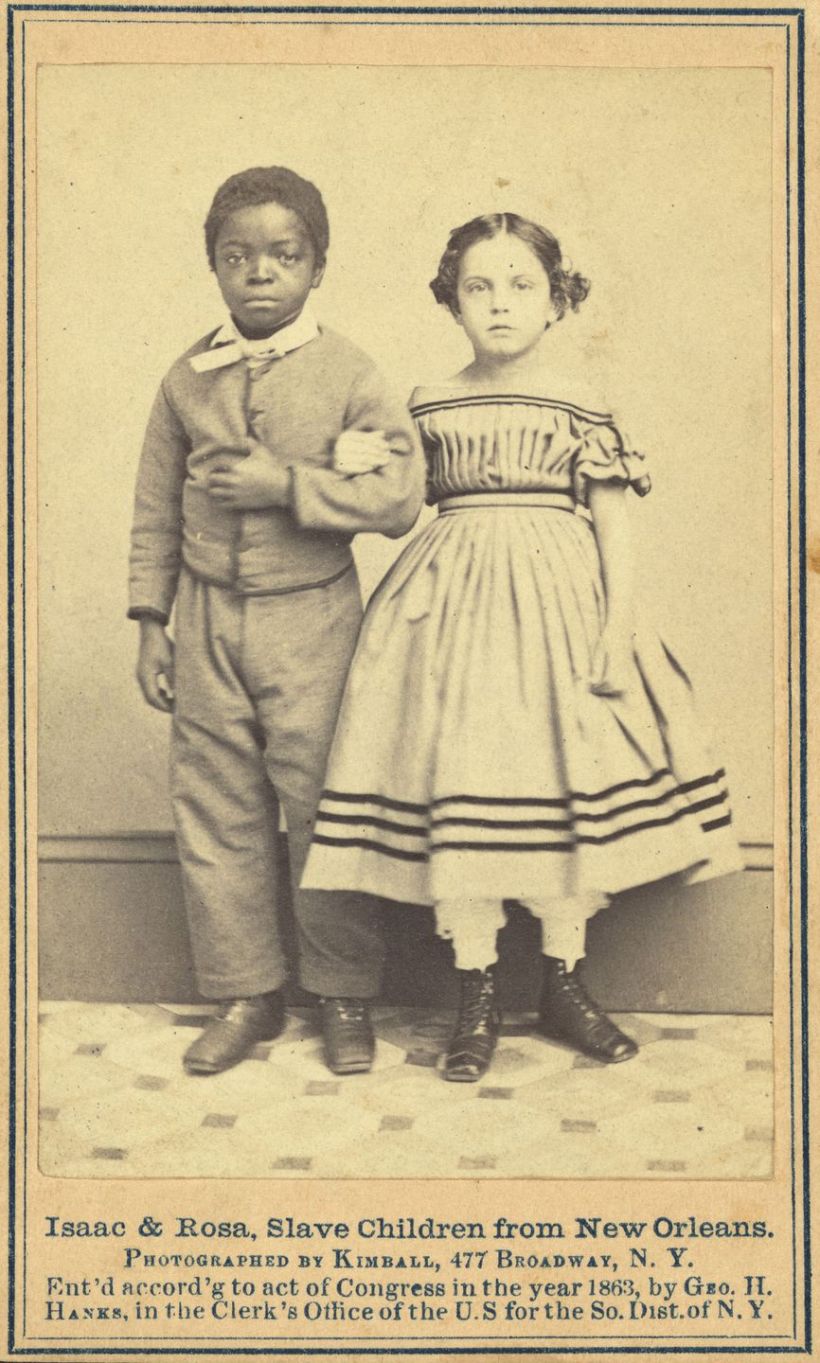

Slaves lived below the decks in conditions of squalor and indescribable horror. Disease spread and ill health was one of the biggest killers. Mortality rates were high, and death made conditions even worse. Many crew members avoided going into the hold because of the smell, the sights, and the sounds below deck. Even though the corpses were thrown overboard, living slaves might be shackled for hours and sometimes days to someone who was dead. From this early start, American slavery was born. Slavery was an institution that lasted for more than three hundred years under which African Americans could expect to be held for life as the property of their masters. This system evolved over time, gradually becoming more strict and regulated. It also varied from owner to owner – some masters may have been more gentle or cruel than others, more generous or stingy with food, etc… But at the end of the day, an enslaved person was regarded by the law as little more than a piece of livestock – property that was totally at the mercy, or lack thereof, of their master.

From this early start, American slavery was born. Slavery was an institution that lasted for more than three hundred years under which African Americans could expect to be held for life as the property of their masters. This system evolved over time, gradually becoming more strict and regulated. It also varied from owner to owner – some masters may have been more gentle or cruel than others, more generous or stingy with food, etc… But at the end of the day, an enslaved person was regarded by the law as little more than a piece of livestock – property that was totally at the mercy, or lack thereof, of their master.

You must be logged in to post a comment.