This lesson was reported from:

A chapter of The United States: An Open Ended History, a free online textbook. Adapted in part from open sources.

For Your Consideration:

-

Generally speaking, what did abolitionists believe? Identify one abolitionist and his or her strategies for achieving this goal.

-

What was the Underground Railroad?

-

What happened at Seneca Falls in 1848?

-

What is a nativist?

-

What was Liberia?

Stirrings of Reform

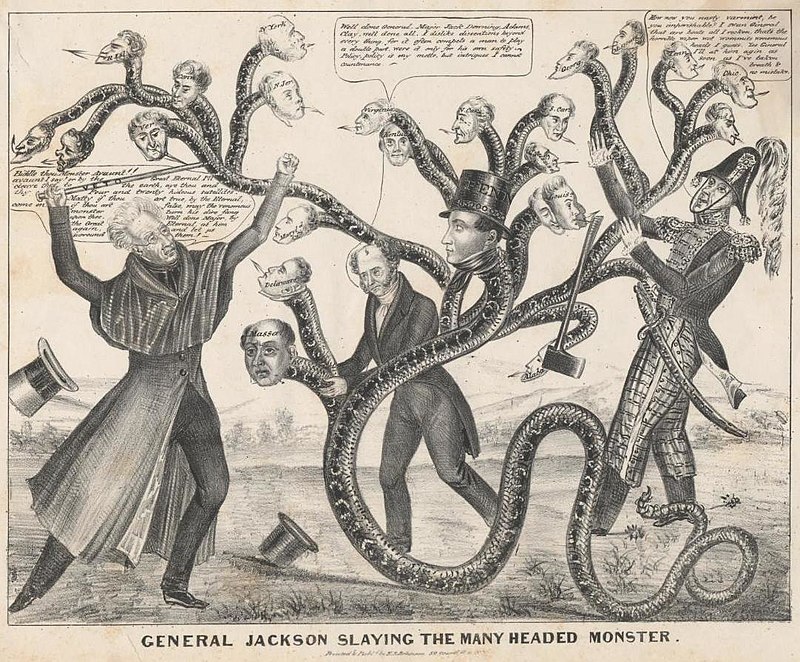

The democratic upheaval in politics exemplified by Jackson’s election was merely one phase of the long American quest for greater rights and opportunities for all citizens. These reformers dedicated their lives – often risked them – to make life as you know it possible…. to give Jefferson’s phrase “all men are created equal” the meaning you understand today – they took his exclusion of women, the poor, people of color, immigrants and others as a challenge, asking “Why not me too?”

The Abolitionists

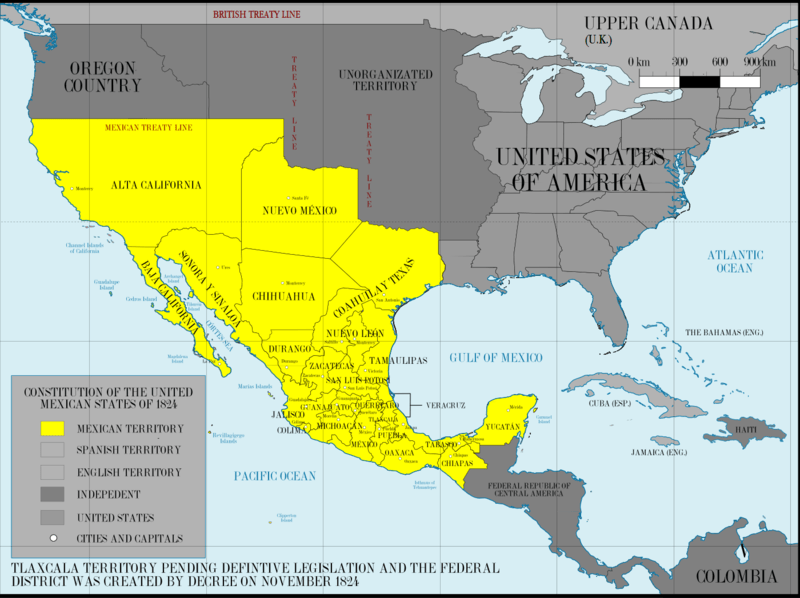

In national politics, Southerners chiefly sought protection and enlargement of the interests represented by the cotton/slavery system. They sought territorial expansion because the wastefulness of cultivating a single crop, cotton, rapidly exhausted the soil, increasing the need for new fertile lands. Moreover, new territory would establish a basis for additional slave states to offset the admission of new free states. In the 1830s Northern opposition to slavery became fierce, even if it was still a minority view. The goal of the antislavery movement was abolition, or the end of slavery, and those who opposed slavery were called abolitionists.

An earlier antislavery movement, an offshoot of the American Revolution, had won its last victory in 1808 when Congress abolished the slave trade with Africa. Thereafter, opposition came largely from the Quakers, who kept up a mild but ineffectual protest. Meanwhile, the cotton gin and westward expansion into the Mississippi delta region created an increasing demand for slaves.

The abolitionist movement that emerged in the early 1830s was combative, uncompromising, and insistent upon an immediate end to slavery. This approach found a leader in William Lloyd Garrison, a young man from Massachusetts, who combined the heroism of a martyr with the crusading zeal of a demagogue. On January 1, 1831, Garrison produced the first issue of his newspaper, The Liberator, which bore the announcement: “I shall strenuously contend for the immediate enfranchisement of our slave population. … On this subject, I do not wish to think, or speak, or write, with moderation. … I am in earnest—I will not equivocate—I will not excuse—I will not retreat a single inch—AND I WILL BE HEARD.”

Garrison’s sensational methods awakened Northerners to the evil in an institution many had long come to regard as unchangeable. He sought to hold up to public gaze the most repulsive aspects of slavery and to castigate slave holders as torturers and traffickers in human life. He recognized no rights of the masters, acknowledged no compromise, tolerated no delay. Other abolitionists, unwilling to subscribe to his law-defying tactics, held that reform should be accomplished by legal and peaceful means. Garrison was joined by another powerful voice, that of Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave who galvanized Northern audiences.

One activity of the movement involved helping slaves escape to safe refuges in the North or over the border into Canada. The Underground Railroad, an elaborate network of secret routes, was firmly established in the 1830s in all parts of the North. In Ohio alone, from 1830 to 1860, as many as 40,000 fugitive slaves were helped to freedom. The number of local antislavery societies increased at such a rate that by 1838 there were about 1,350 with a membership of perhaps 250,000.

Most Northerners nonetheless either held themselves aloof from the abolitionist movement or actively opposed it. In 1837, for example, a mob attacked and killed the antislavery editor Elijah P. Lovejoy in Alton, Illinois.

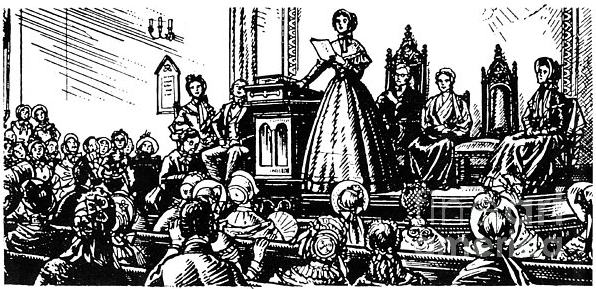

As the Abolition movement became stronger in America, it was expressed in public debate and in petition. During one year, 1830, an anti-slavery petition drive delivered 130,000 petitions to Congress. Pro-slavery forces responded with a series of gag rules that automatically “tabled” all petitions or debate around the subject of limiting slavery, preventing them from being read or discussed. Rather than suppress anti-slavery petitions, however, the gag rules only served to offend Americans from Northern states, and dramatically increase the number of petitions.

Former President John Quincy Adams, elected to the House of Representatives in 1830, fought this so‑called gag rule as a violation of the First Amendment, finally winning its repeal in 1844.

Women’s Rights

Barred from politics and most professions, many women found their voice in church groups, especially those associated with the abolition movement. Calling for the end of slavery brought many women to a realization of their own unequal position in society. From colonial times, unmarried women had enjoyed many of the same legal rights as men, although custom required that they marry early. With matrimony, women virtually lost their separate identities in the eyes of the law. Women were not permitted to vote. Their education in the 17th and 18th centuries was limited largely to reading, writing, music, dancing, and needlework.

The awakening of women began with the visit to America of Frances Wright, a Scottish lecturer and journalist, who publicly promoted women’s rights throughout the United States during the 1820s. At a time when women were often forbidden to speak in public places, Wright not only spoke out, but shocked audiences by her views advocating the rights of women to seek information on birth control and divorce. By the 1840s an American women’s rights movement emerged. Its foremost leader was Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

In 1848 Cady Stanton and her colleague Lucretia Mott organized a women’s rights convention—the first in the history of the world—at Seneca Falls, New York. Delegates drew up a “Declaration of Sentiments,” demanding equality with men before the law, the right to vote, and equal opportunities in education and employment. The resolutions passed unanimously with the exception of the one for women’s suffrage, which won a majority only after an impassioned speech in favor by Frederick Douglass, the black abolitionist.

At Seneca Falls, Cady Stanton gained national prominence as an eloquent writer and speaker for women’s rights. She had realized early on that without the right to vote, women would never be equal with men. Taking the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison as her model, she saw that the key to success lay in changing public opinion, and not in party action. Seneca Falls became the catalyst for future change. Soon other women’s rights conventions were held, and other women would come to the forefront of the movement for their political and social equality.

In 1848 also, Ernestine Rose, a Polish immigrant, was instrumental in getting a law passed in the state of New York that allowed married women to keep their property in their own name. Among the first laws in the nation of this kind, the Married Women’s Property Act encouraged other state legislatures to enact similar laws.

In 1869 Elizabeth Cady Stanton and another leading women’s rights activist, Susan B. Anthony, founded the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), to promote a constitutional amendment for women’s right to the vote. These two would become the women’s movement’s most outspoken advocates. Describing their partnership, Cady Stanton would say, “I forged the thunderbolts and she fired them.”

Education

Public education was common in New England, though it was class-based, with the working class receiving minimum benefits. Schools taught religious values, including corporal punishment and public humiliation.

The spread of suffrage had already led to a new concept of education. Clear-sighted statesmen everywhere understood that universal suffrage required a tutored, literate electorate. Workingmen’s organizations demanded free, tax-supported schools open to all children. Gradually, in one state after another, legislation was enacted to provide for such free instruction. States in the South, however, frequently resisted this impulse for both poor whites and free blacks – more education would have meant less control for the traditional wealthy planter class.

Horace Mann was considered “The Father of American Education.” He wanted to develop a school that would help to get rid of the differences between boys and girls when it came to education. He also felt that this could help keep the crime rate down. He was the first Secretary for the Board of Education in Massachusetts in 1837-1848. He also helped to establish the first school for the education of teachers in America in 1839.

Elsewhere, other educational reforms were taking place during the same period. In 1833 Oberlin College had in attendance 29 men and 15 women. Oberlin college came to be known the first college that allowed women attend. Within five years, thirty-two boarding schools enrolled Indian students. They substituted English for American Indian languages and taught Agriculture alongside the Christian Gospel.

Asylum Movement

Other reformers addressed the problems of prisons and care for the insane. Efforts were made to turn prisons, which stressed punishment, into penitentiaries where the guilty would undergo rehabilitation. In Massachusetts, Dorothea Dix led a struggle to improve conditions for mentally ill persons, who typically were kept confined in wretched prisons alongside actual criminals. After winning improvements in Massachusetts, she took her campaign to the South, where nine states established hospitals for the insane between 1845 and 1852.

Transcendentalism

In the early 1800s, while the Second Great Revival was shaking the country, some people in New England chose another way to faith. Many of them were reading the German Idealists and the Higher Criticism, and some of them had read new English-language translations of Hindu scripture. They were descendants of the people who had come to America to purify their faith. Some of these decided to go further. They called themselves transcendentalists, because they thought they “transcended” any petty doctrine. The Transcendental Club was founded in 1836.

The writer Ralph Waldo Emerson was a major theorist in the movement. He held that God was one, and not the three persons seen in Christian theology. Nor was God a personal being. The great ideas and loves of human beings persisted after their deaths, creating a vast Oversoul. There was no perpetuation of the individual soul. Individuals could move toward the inevitable perfection of their species, and to become one with the Oversoul. Other individuals who held some of Emerson’s beliefs included the feminist Margaret Fuller, Bronson Alcott (whose daughter was the author Louisa May Alcott) and Henry David Thoreau. Different members of the group experimented with vegetarianism, communism, pacifism, free-love, and other non-mainstream practices. Although they differed widely from their revivalist neighbors, many of them also held millenarian views: if only human beings became truly kind and wise, they could create an earthly paradise.

Temperance

Attitudes toward alcohol in America have always been complex, but perhaps no more so than in the mid 1800s. Alcohol was a major source of government tax revenue, and a social force holding communities together. Yet drunkenness, particularly of the poor, began to be commented upon by the middle and upper classes during the late 1700s and 1800s, especially as drinking came to be associated with recent German and Irish immigrants – lesser Americans. During presidential elections, drunkenness was encouraged by political campaigns, and votes were often exchanged for drinks. Many churches came to believe that taverns encouraged business on Sundays, the one day without work, and that people who would have otherwise gone to church spent their money at the bar. As a result of these beliefs, groups began forming in several states to reduce the consumption of alcohol. Although the Temperance movement began with the intent of limiting use, some temperance leaders such as Connecticut minister Lyman Beecher began urging fellow citizens to abstain from drinking in 1825. In 1826, the American Temperance Society formed in a resurgence of religion and morality. By the late 1830s, the American Temperance Society had membership of 1,500,000, and many Protestant churches began to preach temperance.

Immigration

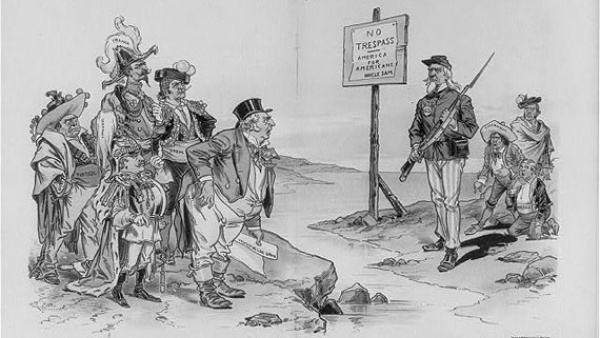

Americans found themselves divided in other, more complex ways. The large number of Catholic immigrants in the first half of the 19th century, primarily Irish and German, triggered a backlash among native-born Protestant Americans. Immigrants brought strange new customs and religious practices to American shores. They competed with the native-born for jobs in cities along the Eastern seaboard. The coming of universal white male suffrage in the 1820s and 1830s increased their political clout. Displaced patrician politicians blamed the immigrants for their fall from power. The Catholic Church’s failure to support the temperance movement gave rise to charges that Rome was trying to subvert the United States through alcohol.

The most important of the nativist – or anti-immigrant – organizations that sprang up in this period was a secret society, the Order of the Star-Spangled Banner, founded in 1849. When its members refused to identify themselves, they were swiftly labeled the “Know-Nothings.” In a few years, they became a national organization with considerable political power.

The Know-Nothings advocated an extension in the period required for naturalized citizenship from five to 21 years. They sought to exclude the foreign-born and Catholics from public office. In 1855 they won control of legislatures in New York and Massachusetts; by then, about 90 U.S. congressmen were linked to the party.

In the early 19th century, a variety of organizations were established that advocated relocation of black people from the United States to places where they would enjoy greater freedom; some endorsed colonization, while others advocated emigration. During the 1820s and 1830s the American Colonization Society (A.C.S.) was the primary vehicle for proposals to “return” black Americans to freedom in Africa, regardless of whether they were native-born in the United States. It had broad support nationwide among white people, including prominent leaders such as Abraham Lincoln, Henry Clay and James Monroe, who considered this preferable to emancipation. Clay said that due to

“unconquerable prejudice resulting from their color, they [the blacks] never could amalgamate with the free whites of this country. It was desirable, therefore, as it respected them, and the residue of the population of the country, to drain them off.”

Many African Americans opposed colonization, and simply wanted to be given the rights of free citizens in the United States.

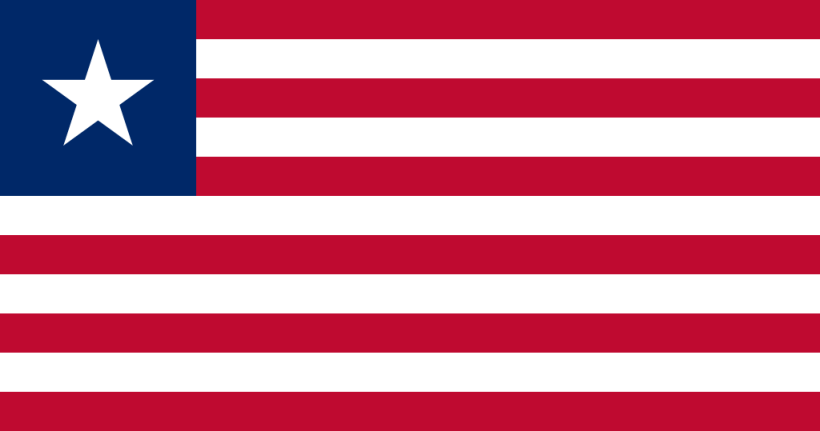

After attempts to plant small settlements on the coast of west Africa, the A.C.S. established the colony of Liberia in 1821–22. Over the next four decades, it assisted thousands of former slaves and free black people to move there from the United States. The tropical disease they encountered was extreme, and most migrants died fairly quickly. American support for colonization waned gradually through the 1840s and 1850s, largely because of the efforts of abolitionists to promote emancipation of slaves and the granting of United States citizenship. The Americo-Liberians established an elite who ruled Liberia continuously until the military coup of 1980.

The article was adapted in part from:

The American force left St. Marks and continued to attack Indian villages. It captured Alexander George Arbuthnot, a Scottish trader who worked out of the Bahamas and supplied the Indians, and Robert Ambrister, a former Royal Marine and self-appointed British agent, as well as the Indian leaders Josiah Francis and Homathlemico. All four were eventually executed. Jackson’s forces also attacked villages occupied by runaway slaves along the Suwannee River.

The American force left St. Marks and continued to attack Indian villages. It captured Alexander George Arbuthnot, a Scottish trader who worked out of the Bahamas and supplied the Indians, and Robert Ambrister, a former Royal Marine and self-appointed British agent, as well as the Indian leaders Josiah Francis and Homathlemico. All four were eventually executed. Jackson’s forces also attacked villages occupied by runaway slaves along the Suwannee River.

You must be logged in to post a comment.