This lesson was reported from:

A chapter of The United States: An Open Ended History, a free online textbook. Adapted in part from open sources.

For Your Consideration:

-

Why was the election of 1824 so controversial?

-

What is nullification? How did Andrew Jackson respond to South Carolina’s attempts to nullify the tariff?

-

Why didn’t President Jackson like the national bank? What did he do to kill it?

-

What was the Indian Removal Act?

-

What was the Trail of Tears?

The 1824 Election and Presidency of John Q. Adams

With the dissolution of the Federalist Party, there were no organized political parties for the 1824 presidential election, and four Democratic-Republicans vied for the office. The Tennessee legislature and a convention of Pennsylvania Democratic-Republicans had nominated General-turned-Senator Andrew Jackson. The Congressional Democratic-Republican caucus selected Treasury Secretary William H. Crawford. Secretary of State John Q. Adams, son of the former President Adams, and House Speaker Henry Clay also joined the contest.

When the electoral votes were cast and counted, no candidate had a majority of votes. Jackson had won the most votes, but Constitutionally, a plurality was not good enough, and the vote for the top three candidates went to the House of Representatives. Clay, with the least amount of votes, was ineligible, but still wielded a lot of power as speaker of the house. And since Clay had a personal dislike of Jackson and supported many of Adams’ policies, which were similar to his American System, Clay threw his support to Adams. Thanks to this support, Adams won the presidency, much to the chagrin of Jackson, who had won the most electoral and popular votes. After Adams appointed Clay as secretary of state, Jackson’s supporters protested that a corrupt bargain had been struck – that Jackson had been robbed of his rightful victory because of dishonest, behind-the-scenes deals made by the elite Adams and Clay.

The 1824 election enabled the resurgence of political parties in America. Jackson’s followers, members of the Democratic Party, were known as Jacksonians; Adams, Clay, and their supporters established the National Republican Party. Partisan politics was back in style in Washington, DC.

During Adams’s administration, new party alignments appeared. Adams’s followers, some of whom were former Federalists, took the name of “National Republicans” as emblematic of their support of a federal government that would take a strong role in developing an expanding nation. Though he governed honestly and efficiently, Adams was not a popular president. He failed in his effort to institute a national system of roads and canals. His coldly intellectual temperament did not win friends. Jackson, by contrast, had enormous popular appeal and a strong political organization. His followers coalesced to establish the Democratic Party, claimed direct lineage from the Democratic-Republican Party of Jefferson, and in general advocated the principles of small, decentralized government.

These factors meant that in the election of 1828, Jackson defeated Adams by an overwhelming electoral majority.

Jackson—Tennessee politician, fighter in wars against Native Americans on the Southern frontier, and hero of the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812—drew his support from poorer white men. He came to the presidency on a rising tide of enthusiasm for popular democracy. The election of 1828 was a significant benchmark in the trend toward broader voter participation. By then most states had either enacted universal white male suffrage or minimized property requirements. In 1824 members of the Electoral College in six states were still selected by the state legislatures. By 1828 presidential electors were chosen by popular vote in every state but Delaware and South Carolina. These developments were the products of a widespread sense that the people should rule and that government by traditional elites had come to an end. Of course, the nation’s definition of “the people” did not include African Americans, Native Americans, or women of any race.

Nullification Crisis

Toward the end of his first term in office, Jackson was forced to confront the state of South Carolina, the most important of the emerging Deep South cotton states, on the issue of the protective tariff. Business and farming interests in the state had hoped that the president would use his power to modify the 1828 act that they called the Tariff of Abominations. In their view, all its benefits of protection went to Northern manufacturers, leaving agricultural South Carolina poorer. In 1828, the state’s leading politician—and Jackson’s vice president until his resignation in 1832—John C. Calhoun had declared in his South Carolina Exposition and Protest that states had the right to nullify oppressive national legislation.

In 1832, Congress passed and Jackson signed a bill that revised the 1828 tariff downward, but it was not enough to satisfy most South Carolinians. The state adopted an Ordinance of Nullification, which declared both the tariffs of 1828 and 1832 null and void within state borders. Its legislature also passed laws to enforce the ordinance, including authorization for raising a military force and appropriations for arms. Nullification – a state’s right to ignore federal laws with which it disagreed – was a long-established theme of protest against perceived excesses by the federal government. Jefferson and Madison had proposed it in the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions of 1798, to protest the Alien and Sedition Acts. The Hartford Convention of 1814 had invoked it to protest the War of 1812. Never before, however, had a state actually attempted nullification. The young nation faced its most dangerous crisis yet.

In response to South Carolina’s threat, Jackson sent seven small naval vessels and a man-of-war to Charleston in November 1832. On December 10, he issued a resounding proclamation against the nullifiers. South Carolina, the president declared, stood on “the brink of insurrection and treason,” and he appealed to the people of the state to reassert their allegiance to the Union. He also let it be known that, if necessary, he personally would lead the U.S. Army to enforce the law.

When the question of tariff duties again came before Congress, Jackson’s political rival, Senator Henry Clay, a great advocate of protection but also a devoted Unionist, sponsored a compromise measure. Clay’s tariff bill, quickly passed in 1833, specified that all duties in excess of 20 percent of the value of the goods imported were to be reduced year by year, so that by 1842 the duties on all articles would reach the level of the moderate tariff of 1816. At the same time, Congress passed a Force Act, authorizing the president to use military power to enforce the laws.

South Carolina had expected the support of other Southern states, but instead found itself isolated. (Its most likely ally, the state government of Georgia, wanted, and got, U.S. military force to remove Native-American tribes from the state.) Eventually, South Carolina rescinded its action. Both sides, nevertheless, claimed victory. Jackson had strongly defended the Union. But South Carolina, by its show of resistance, had obtained many of its demands and had demonstrated that a single state could force its will on Congress.

The Bank War

Although the nullification crisis possessed the seeds of civil war, it was not as critical a political issue as a bitter struggle over the continued existence of the nation’s central bank, the second Bank of the United States. The first bank, established in 1791 under Alexander Hamilton’s guidance, had been chartered for a 20-year period. Though the government held some of its stock, the bank, like the Bank of England and other central banks of the time, was a private corporation with profits passing to its stockholders. Its public functions were to act as a depository for government receipts, to make short-term loans to the government, and above all to establish a sound currency by refusing to accept at face value notes (paper money) issued by state-chartered banks in excess of their ability to redeem.

To the Northeastern financial and commercial establishment, the central bank was a needed enforcer of prudent monetary policy, but from the beginning it was resented by Southerners and Westerners who believed their prosperity and regional development depended upon ample money and credit. The Republican Party of Jefferson and Madison doubted its constitutionality. When its charter expired in 1811, it was not renewed.

For the next few years, the banking business was in the hands of state-chartered banks, which issued currency in excessive amounts, creating great confusion and fueling inflation. It became increasingly clear that state banks could not provide the country with a reliable currency. In 1816 a second Bank of the United States, similar to the first, was again chartered for 20 years. From its inception, the second bank was unpopular in the newer states and territories, especially with state and local bankers who resented its virtual monopoly over the country’s credit and currency, but also with less prosperous people everywhere, who believed that it represented the interests of the wealthy few.

On the whole, the bank was well managed and rendered a valuable service; but Jackson long had shared the Republican distrust of the financial establishment. Elected as a tribune of the people, he sensed that the bank’s aristocratic manager, Nicholas Biddle, was an easy target. When the bank’s supporters in Congress pushed through an early renewal of its charter, Jackson responded with a stinging veto that denounced monopoly and special privilege. The effort to override the veto failed.

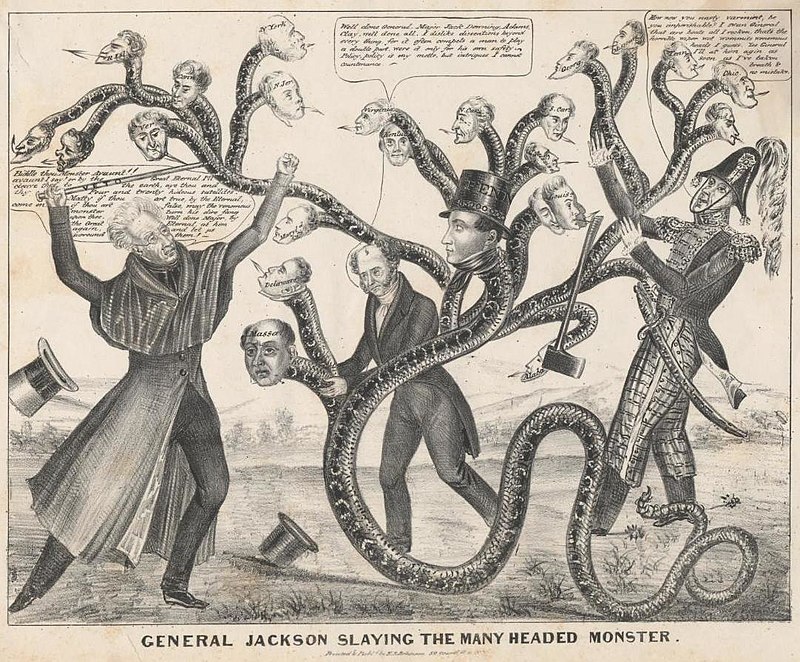

In the presidential campaign of 1832, the bank question revealed a fundamental division. Established merchant, manufacturing, and financial interests favored sound money. Regional bankers and entrepreneurs on the make wanted an increased money supply and lower interest rates. Other debtor classes, especially farmers, shared those sentiments. Jackson and his supporters called the central bank a “monster” and coasted to an easy reelection victory over Henry Clay.

The president interpreted his triumph as a popular mandate to crush the central bank irrevocably. In September 1833 he ordered an end to deposits of government money in the bank, and gradual withdrawals of the money already in its custody. The government deposited its funds in selected state banks, characterized as “pet banks” by the opposition.

For the next generation the United States would get by on a relatively unregulated state banking system, which helped fuel westward expansion through cheap credit but kept the nation vulnerable to periodic panics. During the Civil War, the United States initiated a system of national charters for local and regional banks, but the nation returned to a central bank only with the establishment of the Federal Reserve system in 1913.

The Trail of Tears

In the 1820s, President Monroe’s secretary of war, John C. Calhoun, pursued a policy of removing the remaining tribes from the old Southwest and resettling them beyond the Mississippi. Jackson continued this policy as president. In 1830 Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, providing funds to transport the eastern tribes beyond the Mississippi. In 1834 a special Native-American territory was set up in what is now Oklahoma. In all, the tribes signed 94 treaties during Jackson’s two terms, ceding millions of hectares to the federal government and removing dozens of tribes from their ancestral homelands.

The United States, as it expanded to the west, forcibly removed or killed many Native Americans from their lands as it violated the treaties and Indian rights which both parties had agreed upon. In this way, the concerns of white landowners were considered above the interests of the Indians. In Georgia, for instance, the governor ordered the Cherokee to vacate their lands so the territory would be able to be redistributed to poor Georgians. The Cherokee refused, as they contended that a treaty with the United States that had been signed earlier guaranteed their right to the land. Through a friend of the tribe, they brought their case all the way to the Supreme Court.

In 1832, when Andrew Jackson was President, the Supreme Court ruled that Georgia had acted unconstitutionally. However, Jackson refused to enforce the Court’s ruling. Meanwhile, Congress had passed the Indian Removal Act, which granted reservation land to Native Americans who relocated to territory west of the Mississippi. Under the law, Native Americans could have stayed and became citizens of their home states. The removal was supposed to be peaceful and by their own will, but Jackson forced them to go west.

The Cherokee were forced out of Georgia and had to endure a brutal and deadly trip to the area comprising present-day Oklahoma, a journey which they called the Trail of Tears. Between 2,000 and 4,000 of the 16,000 migrating Cherokees died during the journey, including women, children, and elderly members of the tribe. The conditions were horrible. They were exposed to disease and starvation on their way to the makeshift forts that they would live in. The Cherokees weren’t the only tribe that was forced to leave their homelands. The Choctaws, Creeks, Seminoles, and Chickasaws were also forced to migrate west. The Choctaws were forced to move first in the winter of 1831 and 1832 and many would die on the forced march. The Creek nation would resist the government in Alabama until 1836 but the army eventually pushed them towards Oklahoma. In the end the Natives forced to move traded about 100 million acres for about 32 million acres and about 65 million dollars total for all Native tribes forced to move. This forced relocation of the American Indians was only a chapter in the cruelty given to the Natives by the American government. These forced migrations would have a terrible effect on the Natives as many were victim to disease, starvation, and death.

Seminole Wars

The Seminole Nation in Florida also resisted forced migration. Osceola who was the leader of the Seminoles waged a fierce guerrilla war against federal troops in 1835. The Seminole forces included Creeks, Seminoles, and even African Americans. Osceola would be captured by the US Army under a false white flag of truce. He would die in a POW camp in 1838. However, the Seminoles continued to fight under Chief Coacoochee and other leaders. Finally, in 1842, after much violence on both side, the US would cease its removal efforts. Some Seminoles would remain in Florida to this day near the Everglades.

The article was adapted in part from:

You must be logged in to post a comment.