This lesson is continued from The Brutality of the Philippine-American War. It is a part of a larger unit on the Philippines: At the Crossroads of the World. It is also written to be utilized independently.

This lesson was reported from:

Adapted in part from open sources.

American Criticism

- What does Mark Twain think about the idea of American Empire? Do you agree?

- The political cartoon at the end of this section makes the argument that the United States has always been about expansion by any means necessary, whether they be financial, diplomatic, or conquest. In contrast to Mark Twain’s point of view, “Empire is American,“ the author is arguing – just ask the Native Americans or the Mexicans. How do you respond to this argument?

- In the Twenty-First Century, does the United States have an empire?

Not all Americans cheered the conquest of the Philippines by the United States.

The American Anti-Imperialist League was an organization established on June 15, 1898, to argue and campaign against the American annexation of the Philippines. The Anti-Imperialist League opposed colonial expansion, believing that imperialism violated the fundamental principle that just republican government must derive from “consent of the governed.” The League argued that such activity would necessitate the abandonment of American ideals of self-government and non-intervention—ideals expressed in the United States Declaration of Independence, George Washington’s Farewell Address and Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address.

Perhaps one America’s greatest celebrities at the time was the author Mark Twain, a fierce critic of the U.S. war in the Philippines, who wrote:

“…I have seen that we do not intend to free, but to subjugate the people of the Philippines. We have gone to conquer, not to redeem… And so I am an anti-imperialist. I am opposed to having the [American] eagle put its talons on any other land.”

On October 6, 1900, he published an editorial in the New York World:

“There is the case of the Philippines. I have tried hard, and yet I cannot for the life of me comprehend how we got into that mess. Perhaps we could not have avoided it—perhaps it was inevitable that we should come to be fighting the natives of those islands—but I cannot understand it, and have never been able to get at the bottom of the origin of our antagonism to the natives. I thought we should act as their protector—not try to get them under our heel. We were to relieve them from Spanish tyranny to enable them to set up a government of their own, and we were to stand by and see that it got a fair trial. It was not to be a government according to our ideas, but a government that represented the feeling of the majority of the Filipinos, a government according to Filipino ideas. That would have been a worthy mission for the United States. But now—why, we have got into a mess, a quagmire from which each fresh step renders the difficulty of extrication immensely greater. I’m sure I wish I could see what we were getting out of it, and all it means to us as a nation.”

On October 15, Twain continued in the New York Times:

“We have pacified some thousands of the islanders and buried them; destroyed their fields; burned their villages, and turned their widows and orphans out-of-doors; furnished heartbreak by exile to some dozens of disagreeable patriots; subjugated the remaining ten millions by Benevolent Assimilation, which is the pious new name of the musket… And so, by these providences of god — and the phrase is the government’s, not mine — we are a World Power.”

Despite articulate voices like Twain’s, the Anti-Imperialist League was ultimately defeated in the battle of public opinion by a new wave of politicians who successfully advocated the virtues of American territorial expansion in the aftermath of the Spanish–American War – after all, the Republican Party, the party that most strongly advocated for empire, held the White House through the Philippine-American War, despite the best efforts of the League, all the way until 1912.

See more of the imperialist vs. anti-imperialist debate with Stereoscopic Visions of War and Empire.

Read more at “The White Man’s Burden”: Kipling’s Hymn to U.S. Imperialism.

Decline and Fall of the First Philippine Republic

- Do you take Aguinaldo’s Proclamation of Formal Surrender statement to be sincere – or something he was compelled to say by his captors?

- In your opinion, did the Filipino resistance ever have a chance of success? Did the loss of life that resulted from this conflict accomplish anything?

While this argument played out in American newspapers and polling booths, the Philippine Army continued suffering defeats from the better armed United States Army during the conventional warfare phase. This steady string of setbacks forced Philippine President Emilio Aguinaldo to continually change his base of operations, which he did for nearly the length of the entire war.

On March 23, 1901, General Frederick Funston and his troops captured Aguinaldo in Palanan, Isabela, with the help of some Filipinos (called the Macabebe Scouts after their home locale) who had joined the Americans’ side. The Americans pretended to be captives of the Scouts, who were dressed in Philippine Army uniforms. Once Funston and his “captors” entered Aguinaldo’s camp, they immediately fell upon the guards and quickly overwhelmed them and the weary Aguinaldo.

On April 1, 1901, at the Malacañan Palace in Manila, Aguinaldo swore an oath accepting the authority of the United States over the Philippines and pledging his allegiance to the American government. On April 19, he issued a Proclamation of Formal Surrender to the United States, telling his followers to lay down their weapons and give up the fight. “Let the stream of blood cease to flow; let there be an end to tears and desolation,” Aguinaldo said. “The lesson which the war holds out and the significance of which I realized only recently, leads me to the firm conviction that the complete termination of hostilities and a lasting peace are not only desirable but also absolutely essential for the well-being of the Philippines.”

The capture of Aguinaldo dealt a severe blow to the Filipino cause, but not as much as the Americans had hoped. General Miguel Malvar took over the leadership of the Filipino government, or what remained of it. He originally had taken a defensive stance against the Americans, but now launched all-out offensive against the American-held towns in the Batangas region. General Vicente Lukbán in Samar, and other army officers, continued the war in their respective areas.

General Bell relentlessly pursued Malvar and his men, forcing the surrender of many Filipino soldiers. Finally, Malvar surrendered, along with his sick wife and children and some of his officers, on April 16, 1902. By the end of the month nearly 3,000 of Malvar’s men had also surrendered. With the surrender of Malvar, the Filipino war effort began to dwindle even further.

Official End to the War

- Who gets to decide when a war is over?

- Why was Sakay labelled a bandit and executed when Aguinaldo and Malvar were both allowed to surrender peacefully?

The Philippine Organic Act—approved on July 1, 1902—ratified President McKinley’s previous executive order which had established the Second Philippine Commission. The act also stipulated that a legislature would be established composed of a popularly elected lower house, the Philippine Assembly, and an upper house consisting of the Philippine Commission. The act also provided for extending the United States Bill of Rights to Filipinos. On July 2, the United States Secretary of War telegraphed that since the insurrection against the United States had ended and provincial civil governments had been established throughout most of the Philippine archipelago, the office of military governor was terminated. On July 4, Theodore Roosevelt, who had succeeded to the U.S. Presidency after the assassination of President McKinley, proclaimed an amnesty to those who had participated in the conflict.

After military rule was terminated on July 4, 1902, the Philippine Constabulary was established as an archipelago-wide police force to control brigandage and deal with the remnants of the insurgent movement. The Philippine Constabulary gradually took over the responsibility for suppressing guerrilla and bandit activities from United States Army units. Remnants of the Katipunan and other resistance groups remained active fighting the United States military or Philippine Constabulary for nearly a decade after the official end of the war. After the close of the war, however, Governor General Taft preferred to rely on the Philippine Constabulary and to treat the irreconcilables as a law enforcement concern rather than a military concern requiring the involvement of the American army.

In 1902, Macario Sakay formed another government, the Republika ng Katagalugan, in Rizal Province. This republic ended in 1906 when Sakay and his top followers were arrested and executed the following year by the American authorities.

In 1905, Filipino labour leader Dominador Gómez was authorised by Governor-General Henry Clay Ide to negotiate for the surrender of Sakay and his men. Gómez met with Sakay at his camp and argued that the establishment of a national assembly was being held up by Sakay’s intransigence, and that its establishment would be the first step toward Filipino independence. Sakay agreed to end his resistance on the condition that a general amnesty be granted to his men, that they be permitted to carry firearms, and that he and his officers be permitted to leave the country. Gómez assured Sakay that these conditions would be acceptable to the Americans, and Sakay’s emissary, General León Villafuerte, obtained agreement to them from the American Governor-General.

Sakay believed that the struggle had shifted to constitutional means, and that the establishment of the assembly was a means to winning independence. As a result, he surrendered on 20 July 1906, descending from the mountains on the promise of an amnesty for him and his officials, and the formation of a Philippine Assembly composed of Filipinos that would serve as the “gate of freedom.” With Villafuerte, Sakay travelled to Manila, where they were welcomed and invited to receptions and banquets. One invitation came from the Constabulary Chief, Colonel Harry H. Bandholtz; it was a trap, and Sakay along with his principal lieutenants were disarmed and arrested while the party was in progress.

At his trial, Sakay was accused of “bandolerismo under the Brigandage Act of Nov. 12, 1902, which interpreted all acts of armed resistance to American rule as banditry.” The American colonial Supreme Court of the Philippines upheld the decision. Sakay was sentenced to death, and hanged on 13 September 1907. Before his death, he made the following statement:

Death comes to all of us sooner or later, so I will face the LORD Almighty calmly. But I want to tell you that we are not bandits and robbers, as the Americans have accused us, but members of the revolutionary force that defended our mother country, the Philippines! Farewell! Long live the Republic and may our independence be born in the future! Long live the Philippines!

He was buried at Manila North Cemetery later that day.

Philippine Independence and Sovereignty (1946)

- When was the Philippines granted self-government?

- What conditions did the United States attach to this independence? In light of these conditions, was this true Philippine independence?

On January 20, 1899, President McKinley appointed the First Philippine Commission (the Schurman Commission), a five-person group headed by Dr. Jacob Schurman, president of Cornell University, to investigate conditions in the islands and make recommendations. In the report that they issued to the president the following year, the commissioners acknowledged Filipino aspirations for independence; they declared, however, that the Philippines was not ready for it. Specific recommendations included the establishment of civilian government as rapidly as possible (the American chief executive in the islands at that time was the military governor), including establishment of a bicameral legislature, autonomous governments on the provincial and municipal levels, and a new system of free public elementary schools.

From the very beginning, United States presidents and their representatives in the islands defined their colonial mission as tutelage: preparing the Philippines for eventual independence. Except for a small group of “retentionists,” the issue was not whether the Philippines would be granted self-rule, but when and under what conditions. Thus political development in the islands was rapid and particularly impressive in light of the complete lack of representative institutions under the Spanish.

By the 1930s, there were three main groups lobbying for Philippine independence – Great Depression-era American farmers competing against tariff-free Filipino sugar and coconut oil; those upset with large numbers of Filipino immigrants who could move easily to the United States, in their changing the U.S.’s racial character and competing with American-born workers; and Filipinos seeking Philippine independence.

The Tydings–McDuffie Act (officially the Philippine Independence Act; Public Law 73-127) approved on March 24, 1934, provided for self-government of the Philippines and for Filipino independence (from the United States) after a period of ten years. World War II intervened, bringing the Japanese occupation between 1941 and 1945. In 1946, the Treaty of Manila (1946) between the governments of the U.S. and the Republic of the Philippines provided for the recognition of the independence of the Republic of the Philippines and the relinquishment of American sovereignty over the Philippine Islands.

However, before the 1946 Treaty was authorized, a secret agreement was signed between Philippine President Osmena and US President Truman. President Osmena “supported U.S. rights to bases in his country by backing them publicly and by signing a secret agreement.” This culminated in the Military Bases Agreement, which was signed and submitted for Senate approval in the Philippines by Osmena’s successor, President Manuel Roxas.

As a result of this agreement, the U.S. retained dozens of military bases in Philippines, including a few major ones. It further required U.S. citizens and corporations be granted equal access with Filipinos to Philippine minerals, forests, and other natural resources. In hearings before the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance, Assistant Secretary of State for Economic Affairs William L. Clayton described the law as “clearly inconsistent with the basic foreign economic policy of this country” and “clearly inconsistent with our promise to grant the Philippines genuine independence.

Despite these inconsistencies, President Roxas did not have objections to most of the United States’ proposed military bases agreement in 1947. Below are some of the demands Roxas approved.

- The United States would acquire the military bases for ninety-nine years (Article 29)

- Clark Air Base would cover 130,000 acres, Olongapo City will be integrated into the Subic Naval Base, and areas surrounding the bases will be under US authority (Article 3)

- The Philippines should seek U.S. approval before granting base rights to third nations (Article 25)

On March 17, Roxas submitted the Military Bases Agreement to the Philippine Senate for approval. The Military Bases Agreement was approved by the Philippine Senate on March 26, 1947, with all eighteen present senators in favor. Three senators did not attend the session in protest.

Philippine Senator Tomas Confesor stated that the military bases were “established here by the United States, not so much for the benefit of the Philippines as for their own.” He cautioned his fellow senators: “We are within the orbit of expansion of the American empire. Imperialism is not yet dead.”

Activities

- There is a long tradition of resistance to colonial rule in the Philippines.

Juan Sumuory is celebrated in the Gallery of Heroes. (Manila, Philippines, 2018.) Couple of this with the country’s strong Catholicism – with its tradition of sainthood and martyrdom – and you have nation that is very aware of those who have sacrificed to advance the cause of the Filipino. Manila’s Rizal Park features the Gallery of Heroes, a row of bust sculpture monuments of historical Philippine heroes. These include: Andres Bonifacio, Juan Sumuroy, Aman Dangat, Marcelo H. Del Pilar, Gregorio Aglipay, Sultan Kudarat, Juan Luna, Melchora Aquino, Rajah Sulayman, and Gabriela Silang. Choose one of these personalities to commemorate in your own classroom. Write a brief description of their accomplishments to accompany a piece of artwork that celebrates their life for those who aren’t aware.

- Jose Rizal never specifically advocated violence or even open revolt against

Jose Rizal famously declined the Spanish offer of a carriage ride to his execution site. Instead, he walked, and today, bronze footprints mark his path from Fort Santiago to today’s Rizal Park, a memorial that literally allows one to walk in the footsteps of a national hero. the Spanish, pushing instead for political reforms within the colonial structure. He wrote with such clarity and passion, however, that he become a symbol to revolutionaries – and this is why the colonial authorities decided he needed to die, in a plan that ultimately backfired, transforming him into a martyr. Debate with your class – “Does a national hero need to be a warrior – a violent figure? If not, why are so many warriors celebrated the world over as national heroes?”

- Rudyard Kipling wrote a famous poem about the U.S. and its conquest of the Philippines. It is called “The White Man’s Burden.” The poem became so famous that it became the subject of parody as well. Read both the poem and one of its parodies and discuss it with your classmates using the included questions to help guide you.

- Stereoscopic Visions of War and Empire – This exhibit juxtaposes the visual message presented by the stereoscopic images with excerpts from the letters written by U.S. soldiers that were first published in local newspapers and later collected in the Anti-Imperialist League’s pamphlet, allowing us to get a glimpse of the Philippine-American War as it was presented to Americans at home, reading the news or entertaining friends in their parlors.

- In The Trenches: Harper’s Weekly Covers the Philippine-American War – How did the American media cover the war in the Philippines? An excerpt from “In The Trenches” by John F. Bass, originally published in Harper’s Weekly.

Read more on this subject -> The Origins of the Philippine-American War ◦ The Brutality of the Philippine-American War ◦ The Philippines in the American Empire ◦ “The White Man’s Burden”: Kipling’s Hymn to U.S. Imperialism ◦ Stereoscopic Visions of War and Empire ◦ In The Trenches: Harper’s Weekly Covers the Philippine-American War ◦ Ninoy and Marcos – “A Pact with the Devil is No Pact at All.”

FURTHER READING

History of the Philippines: From Indios Bravos to Filipinos by Luis Francia.

THIS LESSON WAS INDEPENDENTLY FINANCED BY OPENENDEDSOCIALSTUDIES.ORG.

If you value the free resources we offer, please consider making a modest contribution to keep this site going and growing.

For most of 1899, the revolutionary leadership had viewed

For most of 1899, the revolutionary leadership had viewed

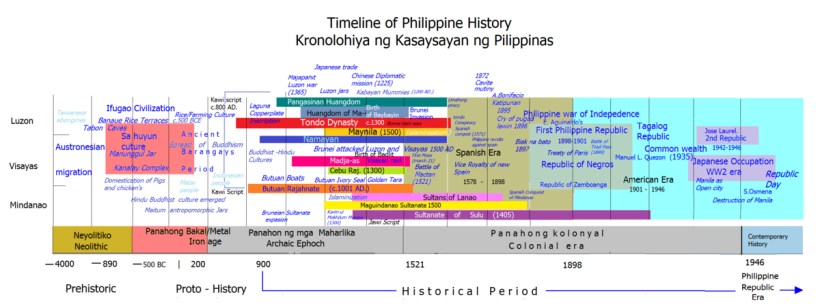

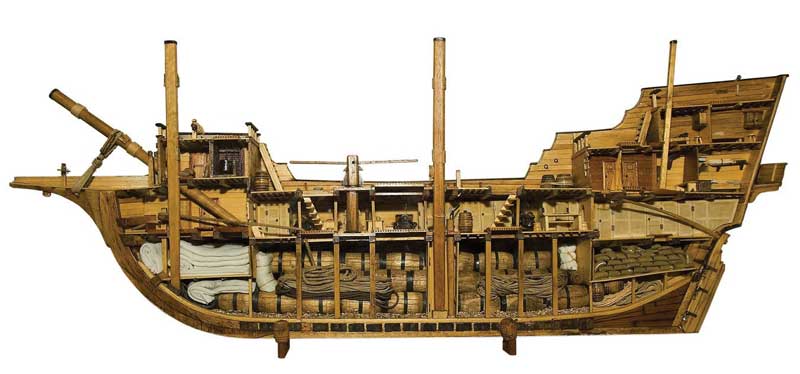

Who are the Filipinos?

Who are the Filipinos?

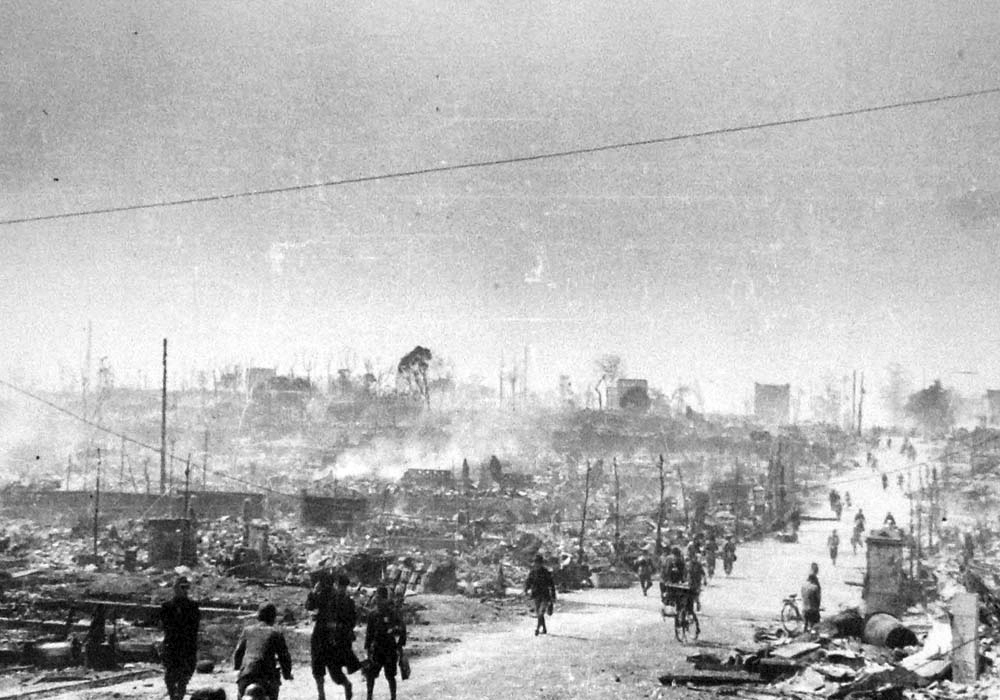

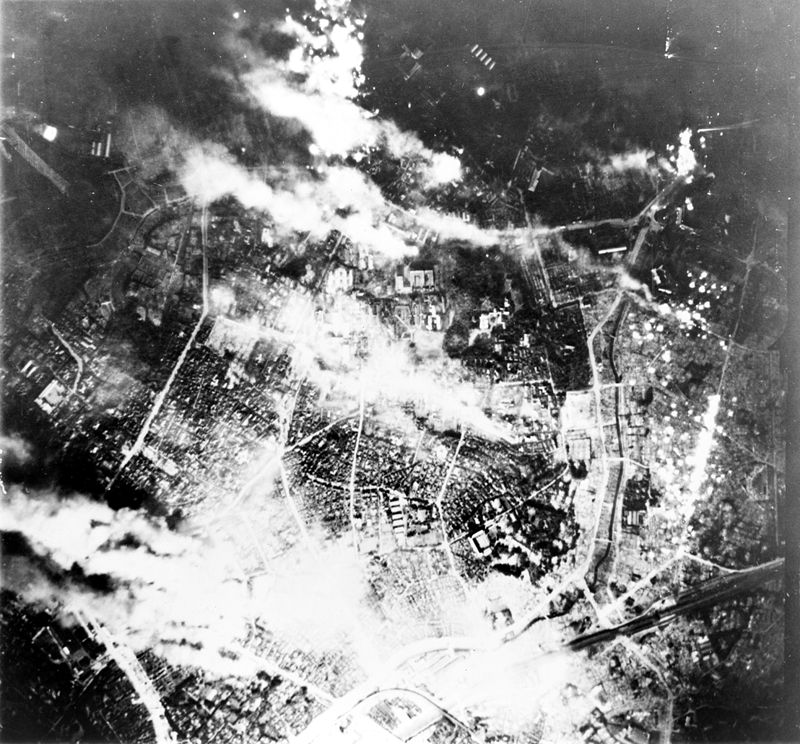

In preparation for firebombing raids, the USAAF tested the effectiveness of incendiary bombs on the adjoining

In preparation for firebombing raids, the USAAF tested the effectiveness of incendiary bombs on the adjoining

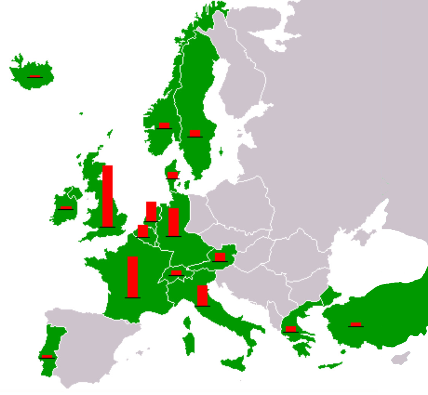

In light of the deteriorating relationship with the Soviet Union and the appearance of Soviet meddling in Greek and Turkish affairs, the withdrawal of British assistance to Greece provided the necessary catalyst for the Truman Administration to reorient American foreign policy. Accordingly, in his speech, President Truman requested that Congress provide $400,000,000 worth of aid to both the Greek and Turkish Governments and support the dispatch of American civilian and military personnel and equipment to the region.

In light of the deteriorating relationship with the Soviet Union and the appearance of Soviet meddling in Greek and Turkish affairs, the withdrawal of British assistance to Greece provided the necessary catalyst for the Truman Administration to reorient American foreign policy. Accordingly, in his speech, President Truman requested that Congress provide $400,000,000 worth of aid to both the Greek and Turkish Governments and support the dispatch of American civilian and military personnel and equipment to the region.

The Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, and with it all of the state-run industries that held a monopoly on the ordinary consumer products that make up this museum’s collection.

The Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, and with it all of the state-run industries that held a monopoly on the ordinary consumer products that make up this museum’s collection.

You must be logged in to post a comment.