Introduction

On the night of March 9, 1945 the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) conducted a devastating firebombing raid on Tokyo, the Japanese capital city. This attack was code-named Operation Meetinghouse by the USAAF and is known as the Great Tokyo Air Raid in Japan. During the raid, bombs dropped from 279 Boeing B-29 Superfortress heavy bombers burned out much of eastern Tokyo. More than 88,000 and possibly over 100,000 Japanese, mostly civilians, were killed and one million left homeless, making it the single most destructive air attack of World War II. The Japanese air and civil defenses proved inadequate, and only 14 American aircraft and 96 airmen were lost.

In many parts of the world, World War II is remembered as a patriotic event – a tie that binds nations together, bringing out a peoples’ best qualities such as heroism, sacrifice, and determination. Such is the case in Russia, where it is remembered literally as the Great Patriotic War. In the United States, the conflict is sometimes termed “the good war,” fought by “the greatest generation.”

But World War II is also notable its sheer ferocity. Brutality became a science on all sides, systematized and streamlined for maximum effect, cranked out on an industrial scale. Perhaps no nation committed so fully to this pursuit than the war’s eventual victor, the United States. With its clockwork air war, refined via the experimental process and statistical analysis, the United States exhibited a chilling commitment to total war against the civilian populations of its enemies.

There is case to be made that this was war – that if the United States had not been so aggressive against Japan and Germany, those nations might have unleashed similar barbarity on the American people. The ends may justify the means…

But it is also worth considering a question posed by Robert McNamara, one of the architects of the bombing campaign against Japan. “What makes it immoral if you lose and not immoral if you win?” he asked.

The U.S. government rightfully condemns the atrocities committed by the Japanese against the civilian populations of China or the Philippines, but it is loathe to grapple with the morality its own actions during the war. This is largely because in the 21st century, the U.S. military continues to rely on many of the same techniques that helped to defeat Japan and Germany so many years ago – that is, the domination of the enemy and any attached civilization populations from the air, be it with incendiary bombs, Agent Orange, napalm, so-called smart missiles, or remotely controlled drones.

To recant on the morality of area bombing of Japan would be to call all of these subsequent strategies into question.

But a free society should never fear honest questions about its conduct – unless it fears the answers.

| READ: | DO: |

| A) Early Incendiary Raids | Plan your own Bombing Raid |

| B) The Attack | Roleplay as a Japanese Citizen |

| C) On the Ground | |

| D) Casualties | |

| E) Reaction |

This lesson was reported from:

Adapted in part from open sources.

A) Early incendiary raids

- How would you describe the planning and preparation that went into the deployment of incendiary bombs against Japan?

- What is the difference between precision bombing and area bombing? How well did precision bombing seem to work in practice? In your opinion, knowing that this will greatly increase the civilian death tool, is this justification to switch to a policy of area bombing?

In June 1944 the USAAF’s XX Bomber Command began a campaign against Japan using B-29 Superfortress bombers flying from airfields in China. Tokyo was beyond the range of Superfortresses operating from China, and was not attacked. This changed in October 1944, when the B-29s of the XXI Bomber Command began moving into airfields in the Mariana Islands. These islands were close enough to Japan for the B-29s to conduct a sustained bombing campaign against Tokyo and most other Japanese cities. The first Superfortress flight over Tokyo took place on November 1, when a reconnaissance aircraft photographed industrial facilities in city.

The attack on Tokyo was an intensification of the air raids on Japan which had commenced in June 1944. Prior to this operation, the USAAF had focused on a precision bombing campaign against Japanese industrial facilities. Precision bombing refers to the attempted aerial bombing of a target with some degree of accuracy, with the aim of maximizing target damage while limiting collateral damage – destroying a single building in a built up area while causing minimal damage to the surrounding neighborhood.

Because of factors like altitude, wind, and limitations in military technology, these attacks were generally unsuccessful, which contributed to the decision to shift to area bombing – the indiscriminate bombing of city blocks or even whole cities – in this case, using firebombs. The operation during the early hours of March 10 was the first major firebombing raid against a Japanese city, and the USAAF units employed significantly different tactics than those used in precision raids including bombing by night. The extensive destruction caused by the raid led these tactics to become standard for the USAAF’s B-29s until the end of the war.

USAAF planners began assessing the feasibility of a firebombing campaign against Japanese cities in 1943. Japan’s main industrial facilities were vulnerable to such attacks as they were concentrated in several large cities, and a high proportion of production took place in homes and small factories in urban areas. The planners estimated that incendiary bomb attacks on Japan’s six largest cities could cause physical damage to almost 40 percent of industrial facilities and result in the loss of 7.6 million man-months of labor. It was also estimated that these attacks would kill over 500,000 people, render about 7.75 million homeless and force almost 3.5 million to be evacuated.

The plans for the strategic bombing offensive against Japan developed in 1943 specified that it would transition from a focus on the precision bombing of industrial targets to area bombing from around halfway in the campaign, which was forecast to be in March 1945. The British and American bombing campaign against Germany also included frequent area bombing of cities, which resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of civilians and massive firestorms in cities such as Hamburg and Dresden.

In preparation for firebombing raids, the USAAF tested the effectiveness of incendiary bombs on the adjoining German and Japanese-style domestic set-piece building complexes at the Dugway Proving Ground during 1943. These trials demonstrated that M69 incendiaries were particularly effective at starting uncontrollable fires. These weapons were dropped from B-29s in clusters, and used napalm as their incendiary filler. After the bomb struck the ground, a fuse ignited a charge which first sprayed napalm from the weapon, and then ignited it.

In preparation for firebombing raids, the USAAF tested the effectiveness of incendiary bombs on the adjoining German and Japanese-style domestic set-piece building complexes at the Dugway Proving Ground during 1943. These trials demonstrated that M69 incendiaries were particularly effective at starting uncontrollable fires. These weapons were dropped from B-29s in clusters, and used napalm as their incendiary filler. After the bomb struck the ground, a fuse ignited a charge which first sprayed napalm from the weapon, and then ignited it.

Several raids were conducted to test the effectiveness of firebombing against Japanese cities. On 3 January, 97 Superfortresses were dispatched on a firebombing raid against Nagoya. This attack started some fires, which were soon brought under control by Japanese firefighters. The success in countering the raid led the Japanese to become over-confident about their ability to protect cities against incendiary raids. The next firebombing raid was directed against Kobe on February 4, and bombs dropped from 69 B-29s started fires which destroyed or damaged 1,039 buildings.

On February 19 the Twentieth Air Force issued a new targeting directive for XXI Bomber Command. While the Japanese aviation industry remained the primary target, the directive placed a stronger emphasis on firebombing raids against Japanese cities. The directive also called for a large-scale trial incendiary raid as soon as possible. This attack was made against Tokyo on 25 February. A total of 231 B-29s were dispatched, of which 172 arrived over the city; this was XXI Bomber Command’s largest raid up to that time. The attack was conducted in daylight, with the bombers flying in formation at high altitudes. It caused extensive damage, with almost 28,000 buildings being destroyed. This was the most destructive raid to have been conducted against Japan, and LeMay and the Twentieth Air Force judged that it demonstrated that large-scale firebombing raids were an effective tactic.

The failure of a precision bombing attack on an aircraft factory in Tokyo on March 4 marked the end of the period in which XXI Bomber Command primarily conducted such raids. Civilian casualties during these operations had been relatively low; for instance, all the raids against Tokyo prior to March 10 caused 1,292 deaths in the city.

B) The Attack

- Describe the technical aspects of the U.S. attack on Tokyo. How much of the attack was improvised, and how much of it was carefully orchestrated?

On March 8 LeMay issued orders for a major firebombing attack on Tokyo the next night. The raid was to target a rectangular area north-eastern Tokyo designated Zone I by the USAAF which measured approximately 4 miles (6.4 km) by 3 miles (4.8 km). It was mainly residential and, with a population of around 1.1 million, was one of the most densely populated urban areas in the world. Zone I contained few militarily significant industrial facilities, though there were a large number of small factories which supplied Japan’s war industries. The area was highly vulnerable to firebombing, as most buildings were constructed from wood and bamboo and were closely spaced. The orders for the raid issued to the B-29 crews stated that the main purpose of the attack was to destroy the many small factories located within the target area, but also noted that it was intended to cause civilian casualties as a means of disrupting production at major industrial facilities.

The B-29s in the squadrons which were scheduled to arrive over Tokyo first were armed with M47 bombs; these weapons used napalm and were capable of starting fires which required mechanized firefighting equipment to control. The bombers in the other units were loaded with clusters of M69s. The planes were each loaded with between five and seven tons of bombs.

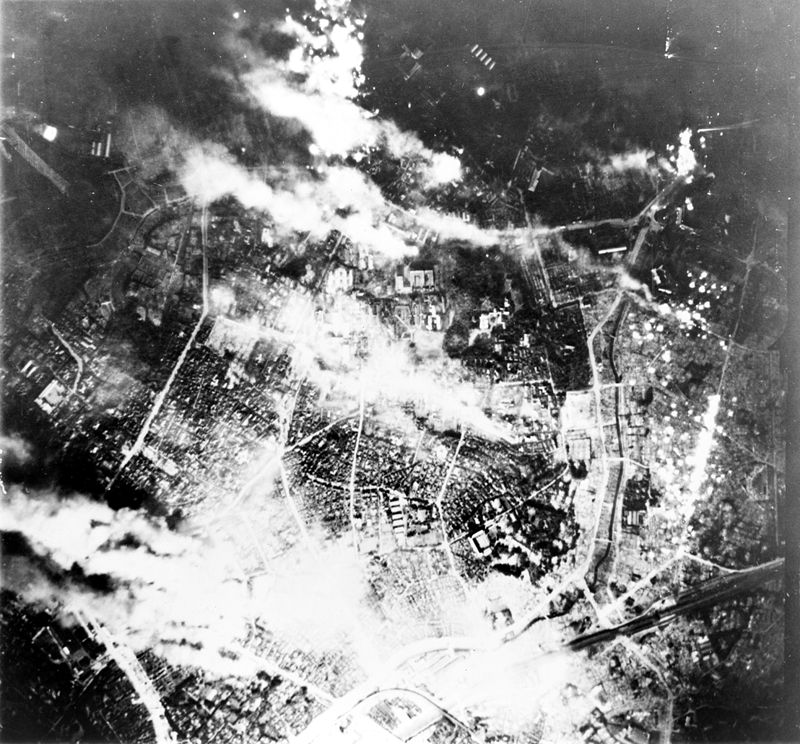

The attack on Tokyo commenced at 12:08 am local time on March 10. Pathfinder bombers simultaneously approached the target area at right angles to each other. Their M47 bombs rapidly started fires in an X shape, which was used to direct the attacks for the remainder of the force. Each of XXI Bomber Command’s wings and their subordinate groups had been briefed to attack different areas within the X shape to ensure that the raid caused widespread damage. As the fires expanded, the American bombers spread out to attack unaffected parts of the target area. Power’s B-29 circled Tokyo for 90 minutes, with a team of cartographers who were assigned to him mapping the spread of the fires.

The raid lasted for approximately two hours and forty minutes. Visibility over Tokyo decreased over the course of the raid due to the extensive smoke over the city. This led some American aircraft to bomb parts of Tokyo well outside the target area. The heat from the fires also resulted in the final waves of aircraft experiencing heavy turbulence. Some American airmen also needed to use oxygen masks when the odor of burning flesh entered their aircraft.

A total of 279 B-29s attacked Tokyo. As expected by LeMay, the defense of Tokyo was not effective. Many American units encountered considerable antiaircraft fire, but it was generally either aimed at altitudes above or below the bombers and reduced in intensity over time as many gun positions were overrun by fires. Nevertheless, the Japanese gunners shot down 12 B-29s.

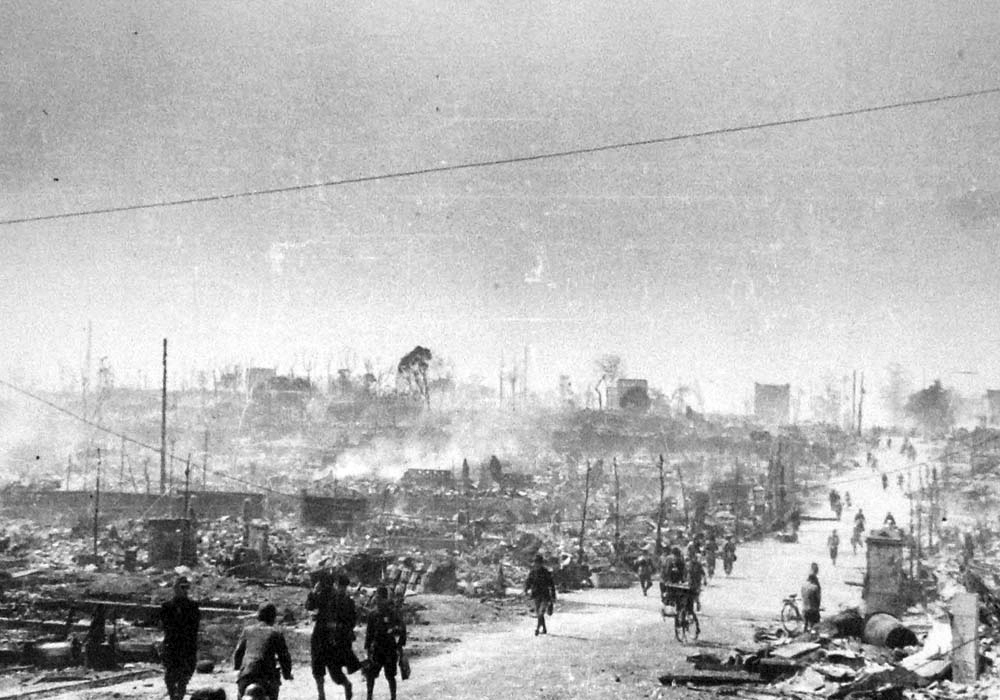

C) On the ground

- What was the effect of the attack?

- Should civilians be considered as fair targets in time of war?

Widespread fires rapidly developed across north-eastern Tokyo. Within 30 minutes of the start of the raid the situation was beyond the fire department’s control. An hour into the raid the fire department abandoned its efforts to stop the conflagration. Instead, the firemen focused on guiding people to safety and rescuing those trapped in burning buildings. Over 125 firemen and 500 civil guards who had been assigned to help them were killed, and 96 fire engines destroyed.

Driven by the strong wind, the large numbers of small fires started by the American incendiaries rapidly merged into major blazes. These formed firestorms which quickly advanced in a north-westerly direction and destroyed or damaged almost all the buildings in their path. By an hour after the start of the attack most of eastern Tokyo had either been destroyed or was being affected by fires.

Civilians who stayed at their homes or attempted to fight the fire had virtually no chance of survival. Historian Richard B. Frank has written that “the key to survival was to grasp quickly that the situation was hopeless and flee.” Soon after the start of the raid news broadcasts began advising civilians to evacuate as quickly as possible, but not all did so immediately.

Thousands of the evacuating civilians were killed. Families often sought to remain with their local neighborhood associations, but it was easy to become separated in the conditions. Few families managed to stay together throughout the night. Escape frequently proved impossible, with roads being rapidly cut by the fires. In many cases entire families were killed.

Many of those who attempted to evacuate to the large parks which had been created as refuges against fires following the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake were killed when the conflagration moved across these open spaces. Others sheltered in solid buildings, such as schools or theatres, and in canals. These were not proof against the firestorm, with smoke inhalation and heat killing large numbers of people in schools. Many of the people who attempted to shelter in canals were killed by smoke or when the passing firestorm sucked oxygen out of the area. However, these bodies of water provided safety to thousands of others. The fire finally burnt itself out during mid-morning on March 10.

D) Casualties

- Why is it hard to estimate the total loss of life during the Tokyo attack of March 9-10?

- American coverage of the bombing of Tokyo – during the war and ever since – typically features photos like the one immediately above. Why wouldn’t war time leaders want to show Americans photos like the one immediately below?

- Look in any American textbook you can find – are there any photos like the one below? Should students be spared seeing the human cost of their country’s wars?

The large scale population movements out of and into Tokyo in the period before the raid, deaths of entire communities and destruction of records mean that it is not possible to know exactly how many died. Most of the bodies which were recovered were buried in mass graves during the days after the raid without being identified. Many bodies of people who had died while attempting to shelter in rivers were swept into the sea and never recovered.

Estimates of the number of people killed in the bombing of Tokyo on 10 March differ. Following the raid 79,466 bodies were recovered and recorded. Many other bodies were not recovered, however, and the city’s director of health estimated that 83,600 people were killed and another 40,918 wounded. The Tokyo fire department put the casualties at 97,000 killed and 125,000 wounded, and the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department believed that 124,711 people had been killed or wounded. Following the war, the United States Strategic Bombing Survey estimated that 87,793 people had been killed and 40,918 injured. The Survey also stated that the majority of the casualties were women, children and elderly people.

American casualties were 96 airmen killed or missing, and 6 wounded or injured.

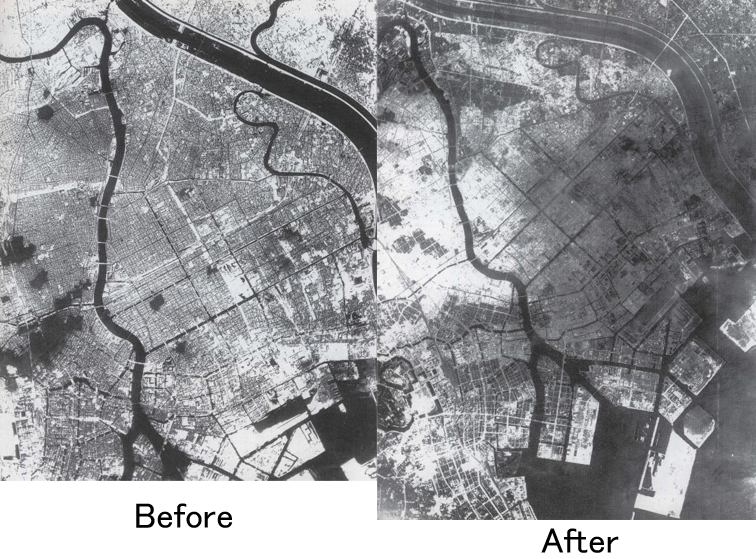

The raid also caused widespread destruction. Police records show that 267,171 buildings were destroyed, and 1,008,005 survivors were rendered homeless. This represents a quarter of all buildings in Tokyo at the time. Most buildings in the Asakusa, Fukagawa, Honjo, Joto and Shitaya wards were destroyed, and seven other districts of the city experienced the loss of around half their buildings. Parts of another 14 wards suffered damage. Overall, 15.8 square miles (41 km2) of Tokyo was burnt out. The number of people killed and area destroyed was the largest of any single air raid of World War II, including the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

While today, those atomic bombings are widely recognized to be uniquely devastating acts – inaccurately remembered as knock-out blows that ended the war, and worthy subject of another lesson – it is important to think of them in the context of the larger fire bombing campaign against Japanese cities. By the time Hiroshima was bombed on August 6, 1945, the Americans had been destroying whole Japanese cities – and their civilian inhabitants – on a regular basis for nearly six months.

E) Reactions

- In your opinion, was the attack on Tokyo a success?

- Imagine you are the President of the United States during World War II – how many Japanese deaths are acceptable to save one American life?

- How would you respond to McNamara’s question?

LeMay considered the operation to have been a significant success on the basis of reports made by the airmen involved and the extensive damage shown in photographs taken by reconnaissance aircraft on March 10. The aircrew who conducted the attack were also pleased with its results. The raid was followed by similar attacks against Nagoya on the night of March 11/12, Osaka in the early hours of March 14, Kobe on March 17/18, and Nagoya again on March 18/19. An unsuccessful night precision raid was also conducted against an aircraft engine factory in Nagoya on March 23/24. The firebombing attacks ended only because XXI Bomber Command’s stocks of incendiaries were exhausted.

Further incendiary attacks were conducted against Tokyo, with the final taking place on the night of May 25/26. By this time, 50.8 percent of the city had been destroyed and more than 4 million people left homeless. Further heavy bomber raids against Tokyo were judged to not be worthwhile, and it was removed from XXI Bomber Command’s target list. By the end of the war, 75 percent of the sorties conducted by XXI Bomber Command had been part of firebombing operations. Few concerns were raised in the United States during the war about the morality of the 10 March attack on Tokyo or the other firebombing raids directed against Japanese cities.

Following the war the bodies which had been buried in mass graves were exhumed and cremated. The ashes were interred at a charnel house in Yokoamicho Park which had originally been established to hold the remains of 58,000 victims of the 1923 earthquake. A Buddhist service has been conducted to mark the anniversary of the raid on 10 March each year since 1951. A number of small neighbourhood memorials were established across the affected area in the years after the raid.

Few other memorials were erected to commemorate the attack in the decades after the war. Efforts began in the 1970s to construct an official Tokyo Peace Museum to mark the raid, but the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly cancelled the project in 1999. Instead, the Dwelling of Remembrance memorial to civilians killed in the raid was built in Yokoamicho Park. This memorial was dedicated in March 2001. The citizens who had been most active in campaigning for the Tokyo Peace Museum established the privately-funded Center of the Tokyo Raids and War Damage, which opened in 2002.

One man who helped to plan the attack on Tokyo was Robert McNamara, an American whose job it was to maximize the destructiveness of U.S. air raids on Japan.

“We burned to death 100,000 Japanese civilians in Tokyo — men, women and children,” he recalled later in life. “LeMay said, ‘If we’d lost the war, we’d all have been prosecuted as war criminals.’ And I think he’s right. He — and I’d say I — were behaving as war criminals.”

“What makes it immoral if you lose and not immoral if you win?” he asked.

As noted in his New York Times obituary, McNamara, who could effectively organize the complex attack described above found this latter question impossible to answer.

Activities

- In a small group, plan your own strategic bombing strike against an enemy city. Your goal is to win the war. Assign each of the following targets a priority rating of one through ten, one being an unacceptable target for attack, to be avoided, and ten being the highest priority for destruction. You may use numbers more than once, but be sure to explain your rationale for assigning each number.

- A steel mill

- A government office

- A military base

- A military hospital

- A factory canning food

- An elementary school

- A high school

- A railroad yard

- A dam

- Workers’ housing near a factory

-

OWI Leaflet #2106 – a warning dropped over Japanese cities on August 1, 1945 in the run up to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. The U.S. military preceded many of its bombing raids by raining cautionary leaflets over Japanese cities. Its Japanese text carried the following warning: “Read this carefully as it may save your life or the life of a relative or friend. In the next few days, some or all of the cities named on the reverse side will be destroyed by American bombs. These cities contain military installations and workshops or factories which produce military goods. We are determined to destroy all of the tools of the military clique which they are using to prolong this useless war. But, unfortunately, bombs have no eyes. So, in accordance with America’s humanitarian policies, the American Air Force, which does not wish to injure innocent people, now gives you warning to evacuate the cities named and save your lives. America is not fighting the Japanese people but is fighting the military clique which has enslaved the Japanese people. The peace which America will bring will free the people from the oppression of the military clique and mean the emergence of a new and better Japan. You can restore peace by demanding new and good leaders who will end the war. We cannot promise that only these cities will be among those attacked but some or all of them will be, so heed this warning and evacuate these cities immediately.” Imagine that you are resident of Tokyo and you find this message in your backyard. Do you believe it? What options for action do you reasonably have? What do you do? Write a short story following this scenario.

THIS LESSON WAS INDEPENDENTLY FINANCED BY OPENENDEDSOCIALSTUDIES.ORG.

If you value the free resources we offer, please consider making a modest contribution to keep this site going and growing.

You can actually visit parts of the world featured in this lesson:

Solemn Feats of the Atomic Tourist – A travel journal documenting a two week educational trip to Kyoto, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki, made in an effort to better understand the legacy of the atomic bombing of Japan, originally published as a zine in 2012.

You must be logged in to post a comment.