This lesson was reported from:

A chapter of The United States: An Open Ended History, a free online textbook. Adapted in part from open sources.

For Your Consideration:

-

What happened at Lexington and Concord that was so different from what came before?

-

How was the Continental Army different from the minutemen?

-

How was the Olive Branch Petition received?

-

What was the main argument and significance of Common Sense?

-

What was the main argument and significance of the Declaration of Independence?

The Battle of Lexington and Concord

General Thomas Gage, an amiable English gentleman with an American-born wife, commanded the garrison at Boston, where political activity had almost wholly replaced trade. Gage’s main duty in the colonies had been to enforce the Coercive Acts. When news reached him that the Massachusetts colonists were collecting powder and military stores at the town of Concord, 32 kilometers away, Gage sent a strong detail to confiscate these munitions.

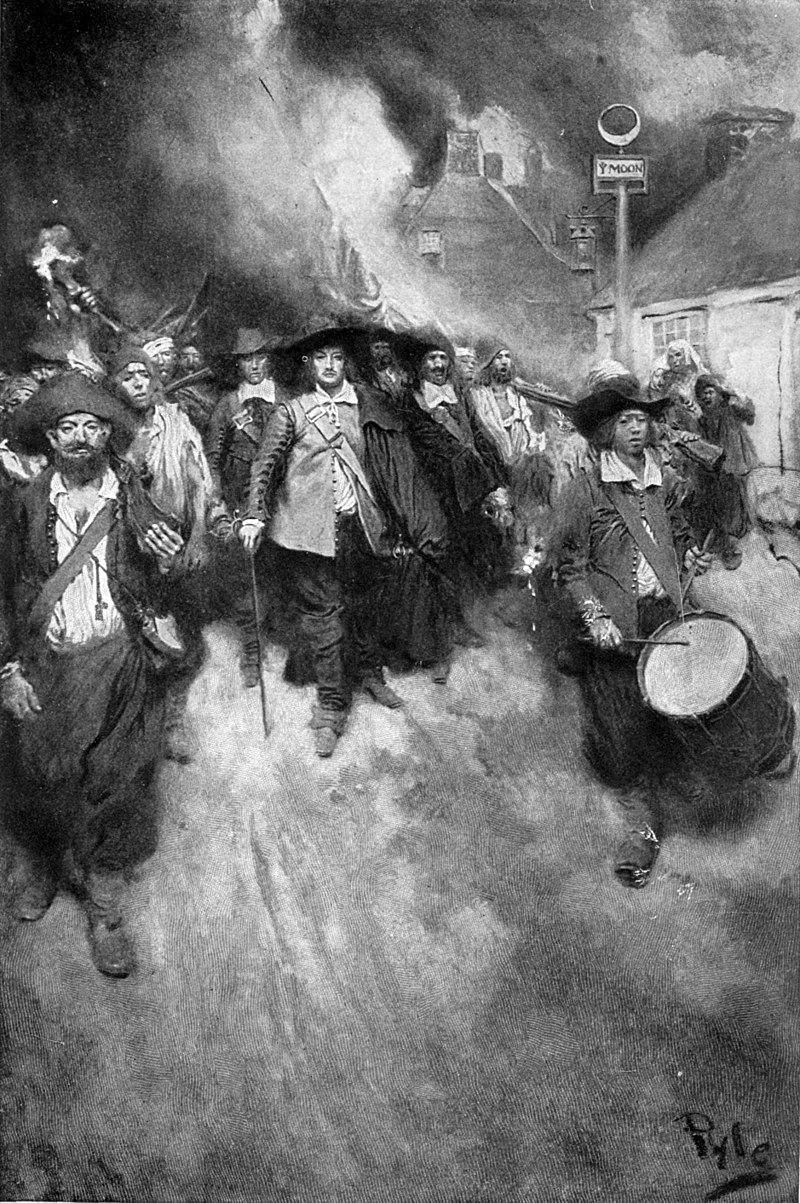

After a night of marching, the British troops reached the village of Lexington on April 19, 1775, and saw a grim band of 77 minutemen— self-trained militiamen charged with defending their hometowns, so named because they were said to be ready to fight in a minute—through the early morning mist. The Minutemen intended only a silent protest, but Marine Major John Pitcairn, the leader of the British troops, yelled, “Disperse, you damned rebels! You dogs, run!” The leader of the Minutemen, Captain John Parker, told his troops not to fire unless fired at first. The Americans were withdrawing when someone fired a shot, which led the British troops to fire at the Minutemen. The British then charged with bayonets, leaving eight dead and 10 wounded. In the often-quoted phrase of 19th century poet Ralph Waldo Emerson, this was “the shot heard round the world” – the moment at which colonial protest crossed the line into outright armed rebellion.

The British pushed on to Concord. The Americans had taken away most of the munitions, but they destroyed whatever was left. In the meantime, American forces in the countryside had mobilized to harass the British on their long return to Boston. All along the road, behind stone walls, hillocks, and houses, militiamen from “every Middlesex village and farm” made targets of the bright red coats of the British soldiers. By the time Gage’s weary detachment stumbled into Boston, it had suffered more than 250 killed and wounded. The Americans lost 93 men.

The Battle of Bunker Hill

On the morning following the Battle of Lexington and Concord, the British woke up to find Boston surrounded by 20,000 armed colonists, occupying the neck of land extending to the peninsula on which the city stood.

The colonist’s action had changed from a battle to a siege, where one army bottles up another in a town or a city. (Though in traditional terms, the British were not besieged, since the Royal Navy controlled the harbor and supplies came in by ship.) The 6,000 to 8,000 rebels faced some 4,000 British regulars under General Thomas Gage. Boston and little else was controlled by British troops.

The Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on May 10. The Congress voted to go to war, inducting the colonial militias into continental service. It appointed Colonel George Washington of Virginia as their commander-in-chief on June 15, promoting to him to rank of General in the Continental Army, the United States’s first national military force.

General Gage countered the siege of Boston on June 17 by attacking the colonists on Breed’s Hill and Bunker Hill. Although the British suffered tremendous casualties compared to the colonial losses, the British were eventually able to dislodge the American forces from their entrenched positions. The colonists were forced to retreat when many colonial soldiers ran out of ammunition. Soon after, the area surrounding Boston fell to the British.

Despite this early defeat for the colonists, the battle proved that they had the potential to counter British forces, which were at that time considered the best in the world.

The Last Chance For Peace

Despite the outbreak of armed conflict, the idea of complete separation from England was still repugnant to many members of the Continental Congress. In July, it adopted the Olive Branch Petition, in which it the Congress affirmed its allegiance to the Crown and asked the king for peace talks. It was received in London at the same time as news of the Battle of Bunker Hill. The King refused to read the petition or to meet with its ambassadors. King George rejected it; instead, on August 23, 1775, he issued a proclamation declaring the colonies to be in a state of rebellion.

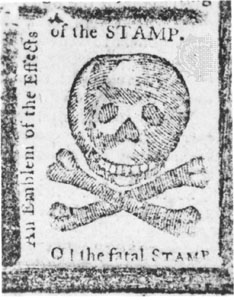

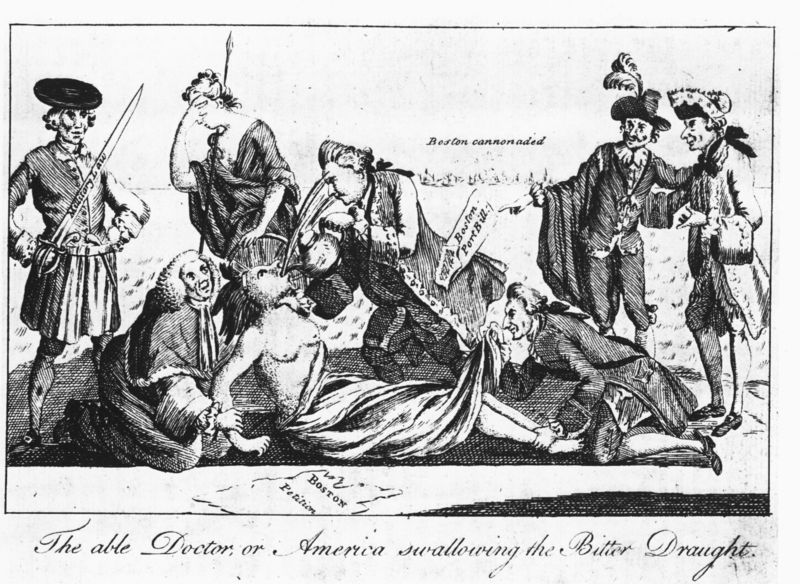

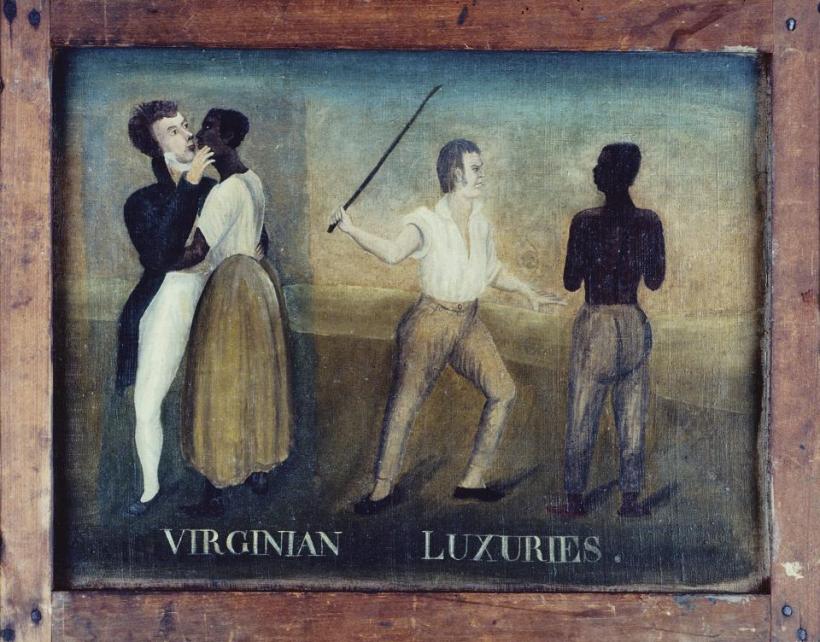

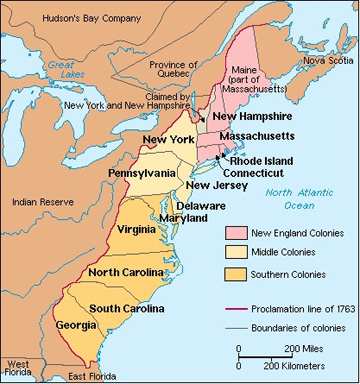

Britain had expected the Southern colonies to remain loyal, in part because of their reliance on slavery. Many in the Southern colonies feared that a rebellion against the mother country would also trigger a slave uprising. In November 1775, Lord Dunmore, the governor of Virginia, tried to capitalize on that fear by offering freedom to all slaves who would fight for the British. Instead, his proclamation drove to the rebel side many Virginians who would otherwise have remained Loyalist.

The Battle for Boston

The British continued to occupy Boston, and despite British control of the harbor, the town and the army were on short rations. Salt pork was the order of the day, and prices escalated rapidly. While the American forces had some information about what was happening in the city, General Gage had no effective intelligence of rebel activities.

On July 3, 1775, George Washington arrived to take charge of the new Continental Army. Forces and supplies came in from as far away as Maryland. Trenches were built at Dorchester Neck, extending toward Boston. Washington reoccupied Bunker Hill and Breeds Hill without opposition. However, these activities had little effect on the British occupation.

In the winter of 1775– 1776, Henry Knox and his engineers, under order from George Washington, used sledges to retrieve sixty tons of heavy artillery that had been captured in surprise attack on the British Fort Ticonderoga, hundreds of miles away in upstate New York. Knox, who had come up with the idea to use sledges, believed that he would have the artillery there in eighteen days. It took six weeks to bring them across the frozen Connecticut River, and they arrived back at Cambridge on January 24, 1776. Weeks later, in an amazing feat of deception and mobility, Washington moved artillery and several thousand men overnight to take Dorchester Heights overlooking Boston. The British fleet had become a liability, anchored in a shallow harbor with limited maneuverability, and under the American guns on Dorchester Heights.

When British General Howe saw the cannons, he knew he could not hold the city. He asked that George Washington let them evacuate the city in peace. In return, they would not burn the city to the ground. Washington agreed: he had no choice. He had artillery guns, but did not have the gunpowder. The whole plan had been a masterful bluff. The siege ended when the British set sail for Halifax, Nova Scotia on March 17, 1776. The militia went home, and in April Washington took most of the Continental Army forces to fortify New York City.

As men continued to fight and die, though, the question became all the more pressing – just what were the colonies trying to achieve? Just what were men fighting and dying for?

Common Sense and Independence

In January 1776, Thomas Paine, a radical political theorist and writer who had come to America from England in 1774, published a 50-page pamphlet, Common Sense. Within three months, it sold 100,000 copies. Paine attacked the idea of a hereditary monarchy, declaring that one honest man was worth more to society than “all the crowned ruffians that ever lived.” He presented the alternatives—continued submission to a tyrannical king and an outworn government, or liberty and happiness as a self-sufficient, independent republic. Circulated throughout the colonies, Common Sense helped to crystallize a decision for separation.

There still remained the task, however, of gaining each colony’s approval of a formal declaration. On June 7, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia introduced a resolution in the Second Continental Congress, declaring, “That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent states. …” Immediately, a committee of five, headed by Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, was appointed to draft a document for a vote.

Largely Jefferson’s work, the Declaration of Independence, adopted July 4, 1776, not only announced the birth of a new nation, but also set forth a philosophy of human freedom that would become a dynamic force throughout the entire world. The Declaration drew upon French and English Enlightenment political philosophy, but one influence in particular stands out: John Locke’s Second Treatise on Government. Locke took conceptions of the traditional rights of Englishmen and universalized them into the natural rights of all humankind. The Declaration’s familiar opening passage echoes Locke’s social-contract theory of government:

We hold these truths to be self‑evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.—That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed,—That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

Jefferson linked Locke’s principles directly to the situation in the colonies. To fight for American independence was to fight for a government based on popular consent in place of a government by a king who had “combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws. …” Only a government based on popular consent could secure natural rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Thus, to fight for American independence was to fight on behalf of one’s own natural rights.

At the signing, Benjamin Franklin is quoted as having replied to a comment by President of the Continental Congress John Hancock that they must all hang together: “Yes, we must, indeed, all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately,” a play on words indicating that failure to stay united and succeed would lead to being tried and executed, individually, for treason.

The article was adapted in part from:

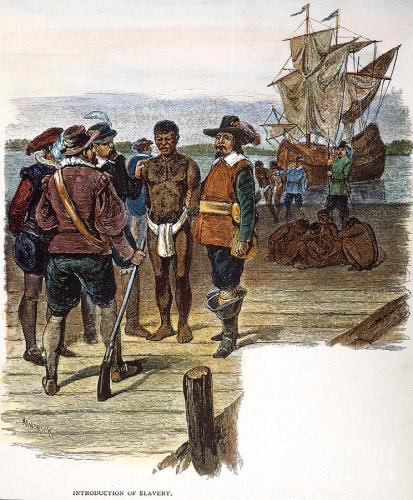

Slaves lived below the decks in conditions of squalor and indescribable horror. Disease spread and ill health was one of the biggest killers. Mortality rates were high, and death made conditions even worse. Many crew members avoided going into the hold because of the smell, the sights, and the sounds below deck. Even though the corpses were thrown overboard, living slaves might be shackled for hours and sometimes days to someone who was dead.

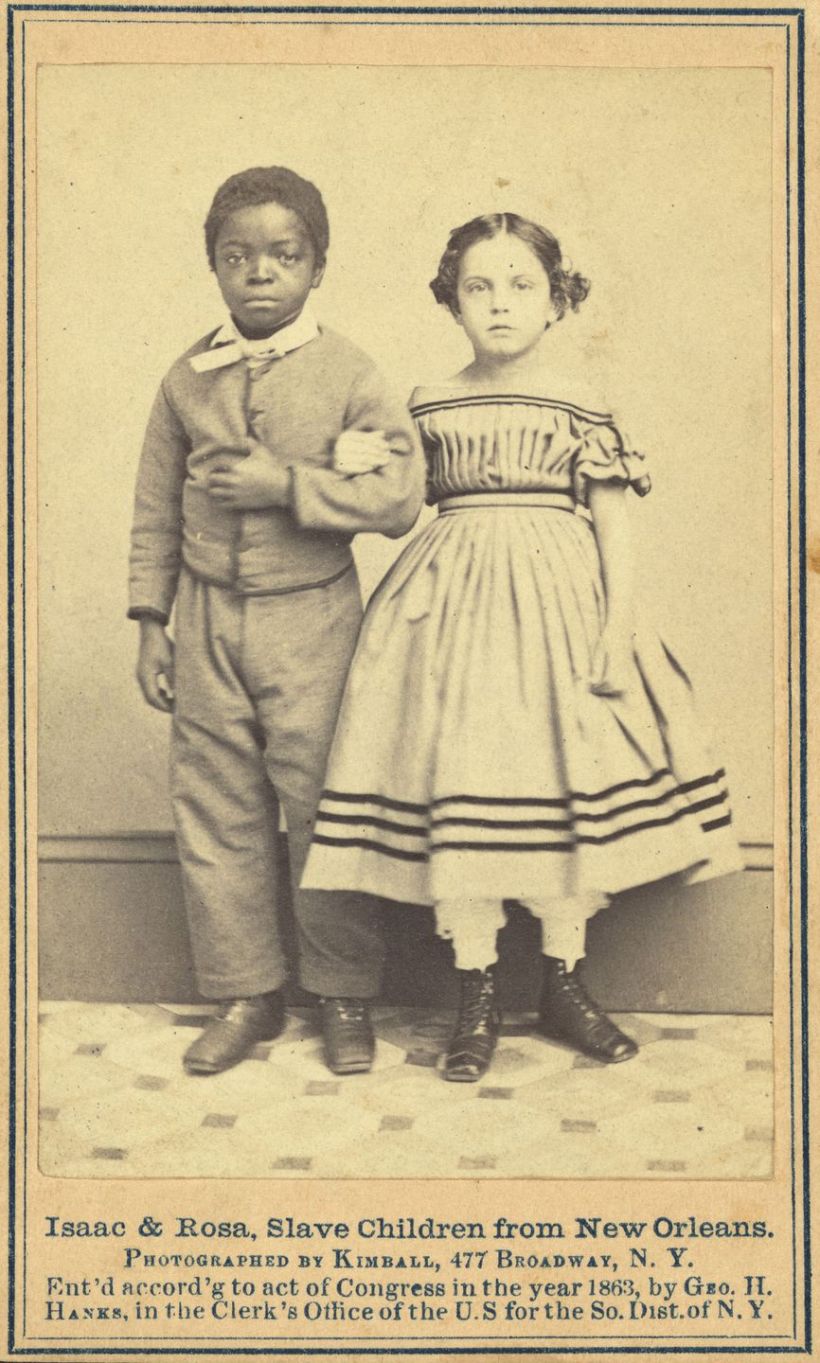

Slaves lived below the decks in conditions of squalor and indescribable horror. Disease spread and ill health was one of the biggest killers. Mortality rates were high, and death made conditions even worse. Many crew members avoided going into the hold because of the smell, the sights, and the sounds below deck. Even though the corpses were thrown overboard, living slaves might be shackled for hours and sometimes days to someone who was dead. From this early start, American slavery was born. Slavery was an institution that lasted for more than three hundred years under which African Americans could expect to be held for life as the property of their masters. This system evolved over time, gradually becoming more strict and regulated. It also varied from owner to owner – some masters may have been more gentle or cruel than others, more generous or stingy with food, etc… But at the end of the day, an enslaved person was regarded by the law as little more than a piece of livestock – property that was totally at the mercy, or lack thereof, of their master.

From this early start, American slavery was born. Slavery was an institution that lasted for more than three hundred years under which African Americans could expect to be held for life as the property of their masters. This system evolved over time, gradually becoming more strict and regulated. It also varied from owner to owner – some masters may have been more gentle or cruel than others, more generous or stingy with food, etc… But at the end of the day, an enslaved person was regarded by the law as little more than a piece of livestock – property that was totally at the mercy, or lack thereof, of their master.

When the Mayflower landed in 1620, Squanto worked to broker peaceable relations between the Pilgrims and the local Pokanokets (a subgroup within the Wampanoag’s orbit). He played a key role in the early meetings in March 1621, partly because he spoke English. He then lived with the Pilgrims for 20 months, acting as a translator, guide, and adviser. He introduced the settlers to the fur trade, and taught them how to sow and fertilize native crops, which proved vital since the seeds which the Pilgrims had brought from England largely failed. Whatever his motivations, with great kindness and patience, Squanto taught the English the skills they needed to survive, including how best to cultivate varieties of the Three Sisters: beans, maize and squash.

When the Mayflower landed in 1620, Squanto worked to broker peaceable relations between the Pilgrims and the local Pokanokets (a subgroup within the Wampanoag’s orbit). He played a key role in the early meetings in March 1621, partly because he spoke English. He then lived with the Pilgrims for 20 months, acting as a translator, guide, and adviser. He introduced the settlers to the fur trade, and taught them how to sow and fertilize native crops, which proved vital since the seeds which the Pilgrims had brought from England largely failed. Whatever his motivations, with great kindness and patience, Squanto taught the English the skills they needed to survive, including how best to cultivate varieties of the Three Sisters: beans, maize and squash.

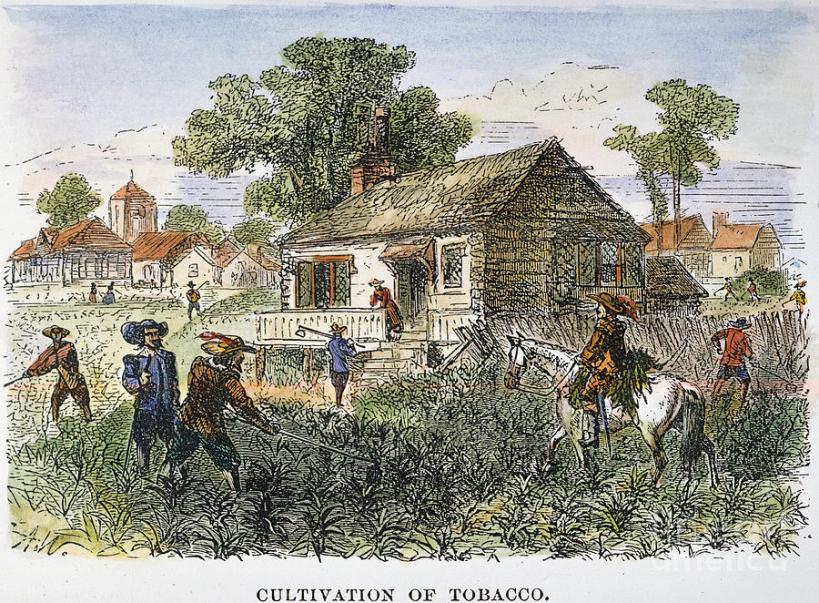

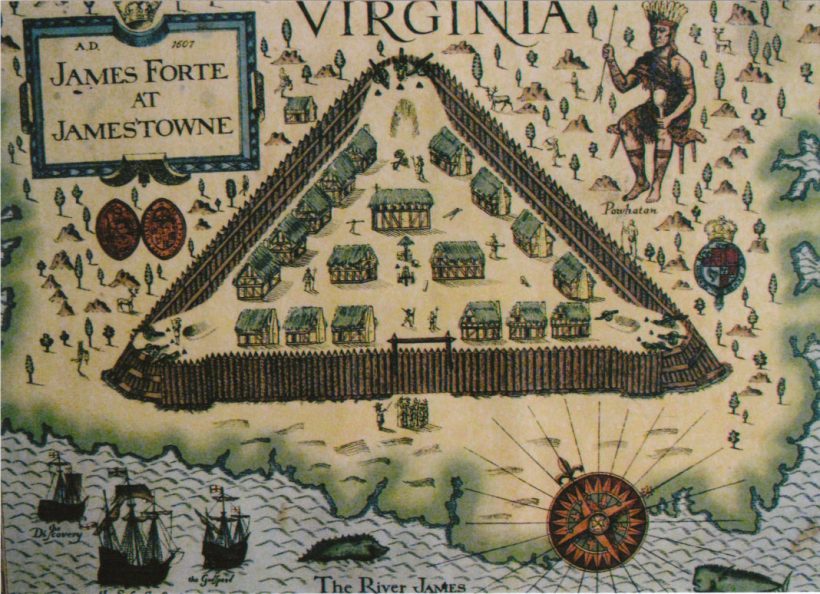

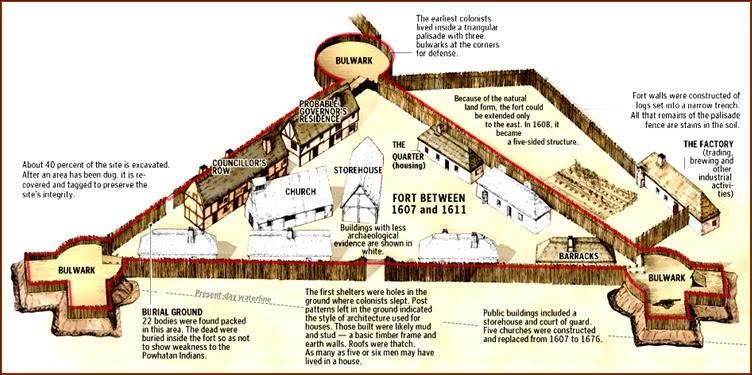

The area laid out in the royal charter was named Virginia, after both the organizing Virginia Company of London and Queen Elizabeth, “the Virgin Queen.” Founded in 1607, the first settlement – a small triangular fort populated by about 100 settlers at the mouth of the James River – was named after King James I. Jamestown was the first permanent English colony in the Americas.

The area laid out in the royal charter was named Virginia, after both the organizing Virginia Company of London and Queen Elizabeth, “the Virgin Queen.” Founded in 1607, the first settlement – a small triangular fort populated by about 100 settlers at the mouth of the James River – was named after King James I. Jamestown was the first permanent English colony in the Americas.

Two men helped the colony to survive: adventurer John Smith and businessman John Rolfe. Smith, who arrived in Virginia in 1608, introduced an ultimatum: “He that will not work, shall not eat”, equivalent to the 2nd Thessalonians 3:10 in the Bible. Under this dire threat, the colonists at last learned how to raise crops and trade with the nearby Indians, with whom Smith had made peace.

Two men helped the colony to survive: adventurer John Smith and businessman John Rolfe. Smith, who arrived in Virginia in 1608, introduced an ultimatum: “He that will not work, shall not eat”, equivalent to the 2nd Thessalonians 3:10 in the Bible. Under this dire threat, the colonists at last learned how to raise crops and trade with the nearby Indians, with whom Smith had made peace.

You must be logged in to post a comment.