This lesson was reported from:

A chapter of The United States: An Open Ended History, a free online textbook. Adapted in part from open sources.

For Your Consideration:

-

What did the Alien and Sedition Acts do? (Name at least two things)

-

How did Madison and Jefferson respond?

-

What happened in the case of Marbury v Madison?

-

What factors caused the use of slavery to increase in the early 1800s?

-

Why did Jefferson purchase Louisiana?

The Adams Presidency

Washington announced his retirement in 1796, firmly declining to serve for more than eight years as the nation’s head. Thomas Jefferson of Virginia (Republican) and John Adams (Federalist) vied to succeed him. Adams won a narrow election victory.

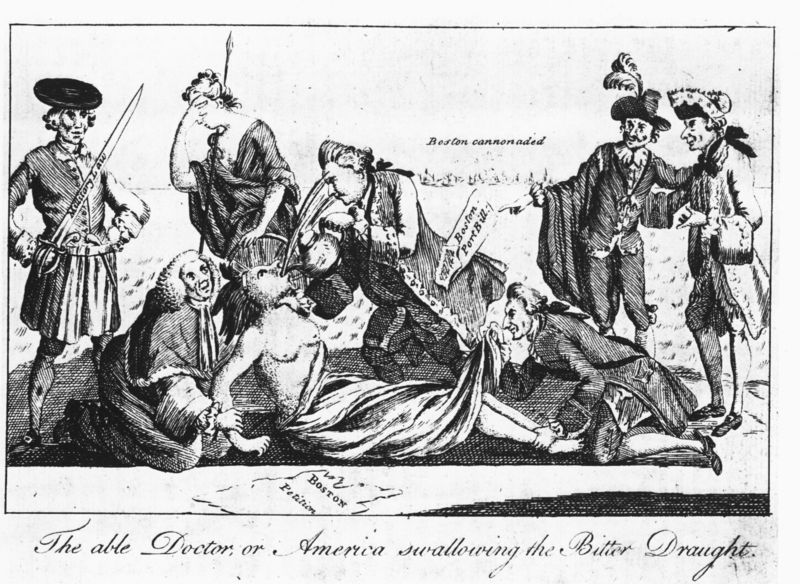

Adams faced serious international difficulties. France, at war with Britain and angered by the fact that the U.S. refused to cut off ties with Britain, began to seize American merchant ships there. By 1797 France had snatched 300 American ships and broken off diplomatic relations with the United States. When Adams sent three commissioners to Paris to negotiate, agents of Foreign Minister Charles Maurice de Talleyrand (whom Adams labeled X, Y, and Z in his report to Congress) informed the Americans that negotiations could only begin if the United States loaned France $12 million and bribed officials of the French government. American hostility to France rose to an excited pitch. Federalists called for war.

These events – the so-called XYZ Affair – led to the strengthening of the fledgling U.S. Armies and Navy.Congress authorized the acquisition of twelve frigates, and made other appropriations to increase military readiness. Despite calls for a formal war declaration, Adams remembered Washington’s farewell address, which warned against getting involved in European conflict, and steadfastly refused to ask Congress for one.

In 1799, after a series of sea battles with the French, war seemed inevitable. In this crisis, Adams rejected the guidance of Hamilton, who wanted war, and reopened negotiations with France. Napoleon, who had just come to power, received them cordially. The danger of conflict subsided with the negotiation of the Convention of 1800, which formally released the United States from its 1778 defense alliance with France. However, reflecting American weakness, France refused to pay $20 million in compensation for American ships taken by the French Navy.

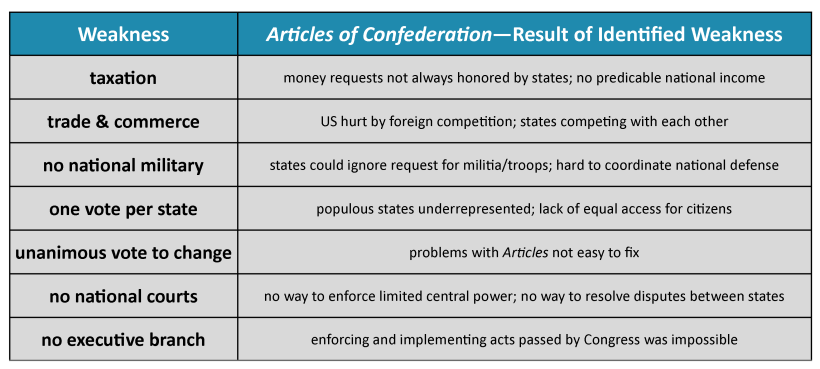

Hostility to France led the Federalist controlled Congress to pass the Alien and Sedition Acts, which had severe repercussions for American civil liberties. The Naturalization Act, which changed the requirement for citizenship from five to 14 years, was targeted at Irish and French immigrants suspected of supporting the Republicans. The Alien Act, operative for two years only, gave the president the power to expel or imprison aliens in time of war. The Sedition Act forbid writing, speaking, or publishing anything of “a false, scandalous, and malicious” nature against the president or Congress. The few convictions won under it created martyrs to the cause of civil liberties and aroused support for the Republicans.

The acts met with resistance. Jefferson – Adams’s own vice-president – and James Madison sponsored the passage of the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions by the legislatures of these two states in November and December 1798. As extreme declarations of states’ rights, the resolutions asserted that states could ignore federal actions if they disagreed with them. This concept of nullification would be used later for the Southern states’ resistance to protective tariffs (favored by the North), and, more ominously, slavery.

Industry and Slavery

In the 1790s certain New England weavers began building large, automated looms, driven by water power. To house them they created the first American factories. Working the looms required less skill and more speed than household laborers could provide. The looms needed people brought to them; and they also required laborers who did not know the origin of the word sabotage. These factories sought out young women.

The factory owners said they wanted to hire these women just for a few years, with the ideal being that they could raise a dowry for their wedding. They were carefully supervised, with their time laid out for them. Some mill owners created evening classes to teach these women how to write and how to organize a household.

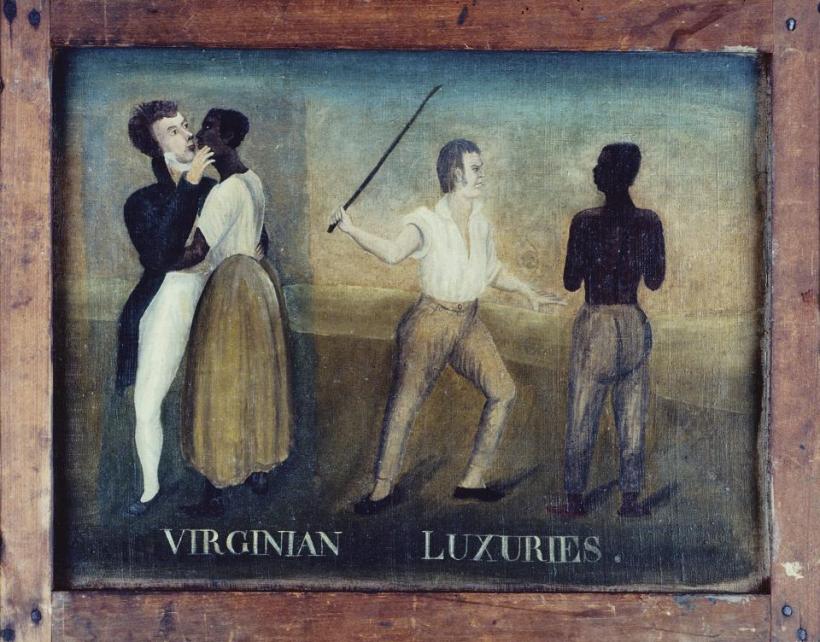

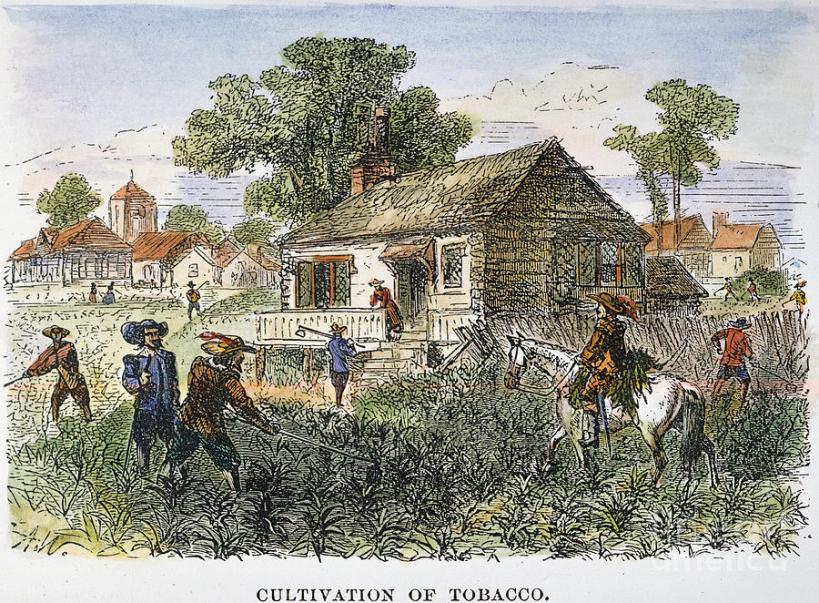

The factories provided a cheaper source of cotton cloth, sent out on ships and on roads improved by a stronger government. For the first time some people could afford more than two outfits, work and Sunday best. They also provided an outlet for cotton from the slave states in the South. Cotton was at that time one among many crops. Many slaves had to work to separate cotton from the seeds of the cotton plant, and to ship it to cloth-hungry New England. This was made simpler by Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin in 1793. Cotton became a profitable crop, and many Southern farms now made it their only crop. Growing and picking cotton was long, difficult labor, and the Southern plantation made it the work for slaves. Northern factories became part of the economy of slavery.

This renewed reliance on slavery went against the trend in other parts of the country. Vermont had prohibited slavery in its state constitution in 1777. Pennsylvania passed laws for the gradual abolition of the condition in 1780, and New York State in 1799. Education, resources, and economic development created the beginnings of industrialization in many Northern states and plantations and slavery and less development in states in the Deep South.

The Election of 1800

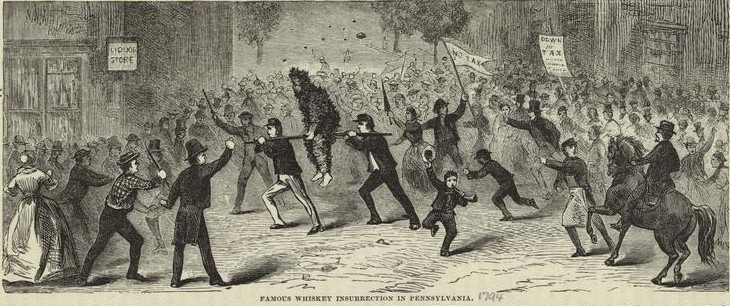

By 1800 the American people were ready for a change. Under Washington and Adams, the Federalists had established a strong government, but sometimes they had followed policies that alienated large groups. For example, in 1798 they had enacted a tax on houses, land, and slaves, affecting every property owner in the country.

The campaign of 1800 was bitter – Jefferson’s allies suggested that President Adams of having a “hideous hermaphroditical character, which has neither the force and firmness of a man, nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman.” Adams’s supporters called Vice President Jefferson “a mean-spirited, low-lived fellow, the son of a half-breed Indian squaw, sired by a Virginia mulatto father.” The two men didn’t speak to each other for another decade.

The Constitution originally called for the individual with the most votes in an election to become President, and for the runner-up to become Vice President. George Washington, who had approved of this system, had justified it by the belief that it worked against factionalism in political parties. However, it had already resulted in the alienation of Vice President Thomas Jefferson under the Adams administration.

In 1800, Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr ran against Adams and his running mate. The two Republican candidates would have preferred for Jefferson to become President and Burr to become Vice President. But the Electoral College vote was tied between the two of them. The Federalist-controlled House of Representatives was called upon to chose between them. It had to vote thirty-six times before Jefferson was chosen to be President, and then only with the reluctant agreement of Alexander Hamilton – to stop Burr, who had refused to concede the presidency to Jefferson as planned. Congress later approved a Constitutional amendment allowing for separate balloting for President and Vice President in the Electoral College.

In Jefferson’s inaugural address, the first such speech in the new capital of Washington, D.C., he promised “a wise and frugal government” that would preserve order among the inhabitants but leave people “otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry, and improvement.” He also spoke of reconciliation after the bitter campaign saying, “We have called by different names brethren of the same principle. We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists.”

Marbury v. Madison

On March 2, 1801, just two days before his presidential term was to end, Adams nominated nearly 60 Federalist supporters to circuit judge and justice of the peace positions the Federalist-controlled Congress had newly created. These appointees—whom Jefferson’s supporters derisively referred to as “the Midnight Judges”—included William Marbury, an ardent Federalist and a vigorous supporter of the Adams presidency.

On March 4, 1801, Thomas Jefferson was sworn in and became the 3rd President of the United States. As soon as he was able, Jefferson instructed his new Secretary of State, James Madison, to withhold the undelivered appointments. In Jefferson’s opinion, the commissions were void because they had not been delivered in time. Without the commissions, the appointees were unable to assume the offices and duties to which they had been appointed. In December 1801, Marbury filed suit against Madison in the Supreme Court, asking the Court to force Madison to deliver Marbury’s commission. This lawsuit resulted in the case of Marbury v. Madison.

The Court did not order Madison to comply. Marshall examined the law Congress had passed that gave the Supreme Court jurisdiction over types of cases like Marbury’s, and found that it had expanded the definition of the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction beyond what was originally set down in the U.S. Constitution. Marshall then struck down the law. This is the origin of the concept of judicial review – the idea that American courts have the power to strike down laws or actions of the government found to violate the Constitution. If the Supreme Court has a super power, it is this, and they discovered it here.

The Louisiana Purchase

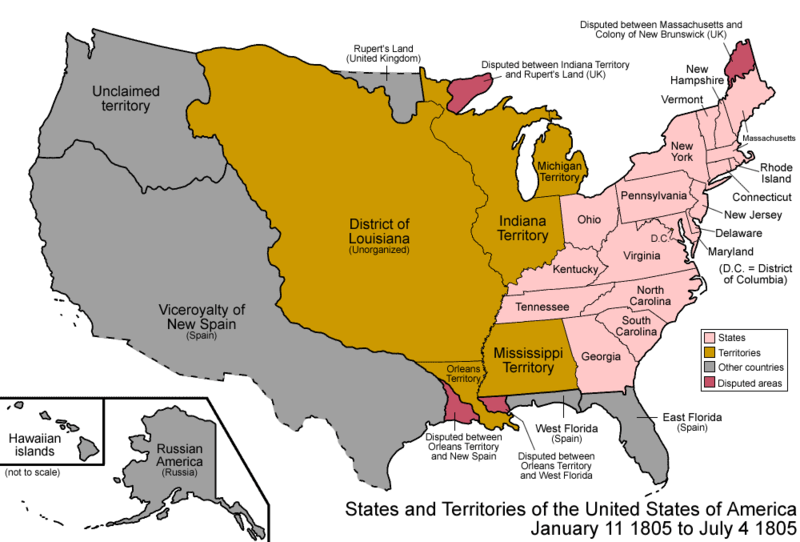

One of Jefferson’s acts doubled the area of the country. At the end of the Seven Years’ War, France had ceded its territory west of the Mississippi River to Spain. Access to the port of New Orleans near its mouth was vital for the shipment of American products from the Ohio and Mississippi river valleys. Shortly after Jefferson became president, Napoleon forced a weak Spanish government to cede this great tract, the Louisiana Territory, back to France. The move filled Americans with apprehension and indignation. French plans for a huge colonial empire just west of the United States seriously threatened the future development of the United States. Jefferson asserted that if France took possession of Louisiana, “from that moment we must marry ourselves to the British fleet and nation.”

Napoleon, however, lost interest after the French were expelled from Haiti by a slave revolt. Knowing that another war with Great Britain was impending, he resolved to fill his treasury and put Louisiana beyond the reach of Britain by selling it to the United States. His offer presented Jefferson with a dilemma: The Constitution conferred no explicit power to purchase territory. At first the president wanted to propose an amendment, but delay might lead Napoleon to change his mind. Advised that the power to purchase territory was an implied power, suggested by the enumerated power to make treaties, Jefferson relented, saying that “the good sense of our country will correct the evil of loose construction when it shall produce ill effects.”

All of this sidestepped the question of whether this land was France’s to sell in the first place – barely any of it was occupied by French people let alone the French army. Instead, it was filled with millions of Native Americans living across hundreds of independent tribes, most of whom had likely never heard of France or the United States.

The United States obtained the “Louisiana Purchase” for $15 million in 1803. It contained more than 2,600,000 square kilometers as well as the port of New Orleans. Once the natives who occupied it had been conquered and removed, the nation would gain a sweep of rich plains, mountains, forests, and river systems that within 80 years would become its heartland—and a breadbasket for the world.

Jefferson commissioned the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1) to explore and map the newly acquired territory, (2) to find a practical route across the western half of the continent, and (3) to establish an American presence in this territory before Britain and other European powers tried to claim it. The campaign’s secondary objectives were scientific and economic: (4) to study the area’s plants, animal life, and geography, and (5) to establish trade with local American Indian tribes.

From May 1804 to September 1806, the Corps of Discovery under the command of Captain Meriwether Lewis and his close friend Second Lieutenant William Clark, was the first American expedition to cross the western portion of the United States. Also along for the mission was York, Clark’s slave, who who carried a gun and hunted on behalf of the expedition and was also accorded a vote during group decisions, more than half a century before African Americans could actually participate in American democracy. Along the way, the Corps picked up they met a French-Canadian fur trapper named Toussaint Charbonneau, and his teenage Shoshone wife Sacagawea, who had purchased as a slave and who was pregnant with their child. The Shoshone lived in the Rocky Mountains, and Sacagawea’s knowledge of nature, geography, language, and culture proved to be invaluable to the expedition.

The Corps met their objective of reaching the Pacific, mapping, and establishing their presence for a legal claim to the land. They established diplomatic relations and trade with at least two dozen indigenous nations. They did not find a continuous waterway to the Pacific Ocean (mostly because one does not exist!) but located an Indian trail that led from the upper end of the Missouri River to the Columbia River which ran to the Pacific Ocean. They gained information about the natural habitat, flora and fauna, bringing back various plant, seed and mineral specimens. They mapped the topography of the land, designating the location of mountain ranges, rivers and the many Indian tribes during the course of their journey. They also learned and recorded much about the language and customs of the American Indian tribes they encountered, and brought back many of their artifacts, including bows, clothing and ceremonial robes.

The article was adapted in part from:

You must be logged in to post a comment.