This lesson was reported from:

Adapted in part from open sources.

- What is the difference between a phonetic sign and a logogram? Which one does English use?

- Why are examples of Maya books so rare?

- Was reading and writing likely a skill practiced by common or poor Maya? Can you think of any modern professions similar to that of scribe?

The Maya writing system (sometimes called hieroglyphs from a superficial resemblance to the Ancient Egyptian writing) is a logosyllabic writing system, which means that it combines phonetic signs (or glyphs) representing sounds and syllables with logograms – glyphs representing entire words. While English uses 26 letters, 10 numerals, and various marks of punctuation, Maya writing is much expansive. At any one time, no more than around 500 glyphs were in use, some 200 of which (including variations) were phonetic.

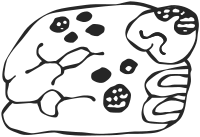

For example, this is the Maya word B’alam – “jaguar” – written logographicaly with the jaguar head glyph standing for the entire word:

Both are pronounced b’alam and carry the same meaning.

The Maya writing system is one of the outstanding achievements of the pre-Columbian inhabitants of the Americas. It was the most sophisticated and highly developed writing system of more than a dozen systems that developed in Mesoamerica. The earliest inscriptions in an identifiable Maya script date back to 300–200 BC.

Unlike our modern base 10 system, the Maya used a base 20 (vigesimal) system. The very concept of a vigesimal system probably stemmed from the full set of human digits: the term for “person,” winik, is indistinguishable from that for a unit of “twenty.”

The bar-and-dot counting system that is the base of Maya numerals was in use in Mesoamerica by 1000 BC; the Maya adopted it by the Late Preclassic, and added the symbol for zero. This may have been the earliest known occurrence of the idea of an explicit zero worldwide, although it may have been predated by the Babylonian system. The earliest explicit use of zero occurred on Maya monuments is dated to 357 AD.

The Maya script was in use up to the arrival of the Europeans, with its use peaking during the Classic Period. In excess of 10,000 individual texts have been recovered, mostly inscribed on stone monuments, lintels, stelae and ceramics. The Maya also produced texts painted on a form of paper manufactured from processed tree-bark generally now known by its Nahuatl-language name amatl used to produce codices. The skill and knowledge of Maya writing persisted among segments of the population right up to the Spanish conquest. The knowledge was subsequently lost, as a result of the impact of the conquest on Maya society.

In an effort to suppress the Maya religion and to forcibly convert the Maya to Christianity, the Catholic Church and colonial officials, notably Bishop Diego de Landa, destroyed Maya texts wherever they found them, and with them the knowledge of Maya writing. By chance three pre-Columbian books dated to the Postclassic period have been preserved. These are known as the Madrid Codex, the Dresden Codex and the Paris Codex. A few pages survive from a fourth, the Grolier Codex. Archaeology conducted at Maya sites often reveals other fragments, rectangular lumps of plaster and paint chips which were codices; these tantalizing remains are, however, too severely damaged for any inscriptions to have survived, with most of the organic material having decayed.

Our knowledge of ancient Maya thought must represent only a tiny fraction of the whole picture, for of the thousands of books in which the full extent of their learning and ritual was recorded, only four have survived to modern times (as though all that posterity knew of ourselves were to be based upon three prayer books and ‘Pilgrim’s Progress’).

— Michael D. Coe, The Maya, London: Thames and Hudson, 6th ed., 1999, pp. 199–200.

According to Spanish accounts, Maya books contained histories, prophecies, maps, tribute ledgers, songs, scientific observations, and genealogies – but only four examples of Maya books have survived to the modern day, and they are all ritual/religious books. Painted pictures and carvings depict Maya books with jaguar-skin covers, painted by specialized scribes using brushes or quills dipped in conch shell inkpots, but as far as we can tell in the modern day, none of these material artifacts has survived the Spanish conquest or the humid jungle.

The decipherment and recovery of the knowledge of Maya writing has been a long and laborious process. Some elements were first deciphered in the late 19th and early 20th century, mostly the parts having to do with numbers, the Maya calendar, and astronomy. Major breakthroughs were made from the 1950s to 1970s, and accelerated rapidly thereafter. By the end of the 20th century, scholars were able to read the majority of Maya texts, and ongoing work continues to further illuminate the content.

Scribes and literacy

Commoners were probably illiterate; scribes were drawn from the elite. It is not known if all members of the aristocracy could read and write, although at least some women could, since there are representations of female scribes in Maya art. Maya scribes were called aj tz’ib, meaning “one who writes or paints.” Although the archaeological record does not provide examples of brushes or pens, analysis of ink strokes on the Postclassic codices suggests that it was applied with a brush with a tip fashioned from pliable hair. There were probably scribal schools where members of the aristocracy were taught to write.

Commoners were probably illiterate; scribes were drawn from the elite. It is not known if all members of the aristocracy could read and write, although at least some women could, since there are representations of female scribes in Maya art. Maya scribes were called aj tz’ib, meaning “one who writes or paints.” Although the archaeological record does not provide examples of brushes or pens, analysis of ink strokes on the Postclassic codices suggests that it was applied with a brush with a tip fashioned from pliable hair. There were probably scribal schools where members of the aristocracy were taught to write.

Although not much is known about Maya scribes, some did sign their work, both on ceramics and on stone sculpture. Usually, only a single scribe signed a ceramic vessel, but multiple sculptors are known to have recorded their names on stone sculpture; eight sculptors signed one stela at Piedras Negras. However, most works remained unsigned by their artists.

Read more on this subject -> The Basics of Ancient Maya Civilization ◦ The Ancient Maya in Time and Space ◦ Ancient Maya Society ◦ The Maya City ◦ The Written Language of the Maya

Activities

- Use this dictionary to write a short poem in the Maya script, using at least a dozen glyphs. Does composing in Mayan effect the experience of writing and reading?

- The Popol Vuh is one of the few remaining Maya stories dating to before the Spanish conquest. It was originally preserved through oral tradition throughout the Maya world until approximately 1550 when it was written down. The Popol Vuh includes the Mayan creation myth, beginning with the exploits of the Hero Twins Hunahpú and Xbalanqué. Read some of an English translation of the Popol Vuh, then choose a scene to reenact in a 3-5 minute skit or video in front of your class.

- Write an essay that compares and contrasts the 16th century Spanish conquistadors and the 21st century Taliban.

- Research the Caste War of Yucatán, which occurred in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula in the nineteenth century. Take inspiration from the form and style of the Dresden Codex to tell the story of this late period Maya resistance.

- Choose any section from this unit and develop a lesson – in the form of a presentation, a storybook, or a worksheet – that teaches younger students about the Maya. Make sure the material is age appropriate in content and approach, and create some simple questions to check your audience’s understanding.

Further Reading

The Maya (People and Places) by Michael Coe.

Ancient Maya by Barbara Somervill.

1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus by Charles C. Mann.

THIS LESSON WAS INDEPENDENTLY FINANCED BY OPENENDEDSOCIALSTUDIES.ORG.

If you value the free resources we offer, please consider making a modest contribution to keep this site going and growing.

You can actually visit parts of the world featured in this lesson:

A Guided Tour of Maya Mexico, 2017 – Explore the ruins of Ek’ Balam, Uxmal, and Chichen Itza, scramble through streets of colonial Merida, and sample the cuisine and culture of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. Supplementary photos and information on the Yucatan, past and present.