What factors account for the rise and fall of ancient societies? What can we learn about such a society from the ruins of its monumental architecture?

This lesson was reported from:

Adapted in part from open sources.

The Khmer Empire, the predecessor state to modern Cambodia, was a powerful Khmer Hindu–Buddhist empire in Southeast Asia. The empire at times ruled over and/or vassalised most of mainland Southeast Asia, parts of modern-day Laos, Thailand, and southern Vietnam.

The beginning of the era of the Khmer Empire is conventionally dated to 802 AD. In this year, king Jayavarman II had himself declared chakravartin (“king of the world”, or “king of kings”). The empire ended with the fall of Angkor in the 15th century.

Angkor (“Capital City”) is an ancient city in modern Cambodia that served as the seat of the Khmer Empire, which flourished from approximately the 9th to 15th centuries. Angkor was a megacity supporting at least 0.1% of the global population during 1010-1220.

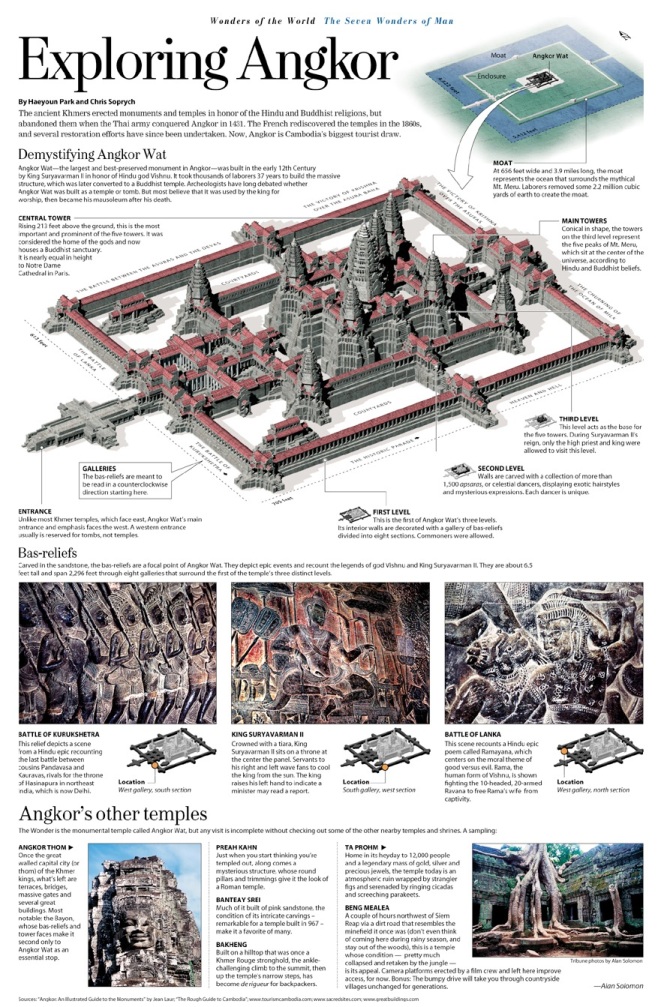

The ruins of Angkor are located amid forests and farmland to the north of the Great Lake (Tonlé Sap) and south of the Kulen Hills, near modern-day Siem Reap city (13°24′N, 103°51′E), in Siem Reap Province. The temples of the Angkor area number over one thousand, ranging in scale from nondescript piles of brick rubble scattered through rice fields to the magnificent Angkor Wat, said to be the world’s largest single religious monument. Many of the temples at Angkor have been restored, and together, they comprise the most significant site of Khmer architecture. Visitors approach two million annually, and the entire expanse, including Angkor Wat and Angkor Thom is collectively protected as a UNESCOWorld Heritage Site. The popularity of the site among tourists presents multiple challenges to the preservation of the ruins.

In 2007, an international team of researchers using satellite photographs and other modern techniques concluded that Angkor had been the largest pre-industrial city in the world, with an elaborate infrastructure system connecting an urban sprawl of at least 1,000 square kilometres (390 sq mi) to the well-known temples at its core. Angkor is considered to be a “hydraulic city” because it had a complicated water management network, which was used for systematically stabilizing, storing, and dispersing water throughout the area. This network is believed to have been used for irrigation in order to offset the unpredictable monsoon season and to also support the increasing population. Although the size of its population remains a topic of research and debate, newly identified agricultural systems in the Angkor area may have supported up to one million people.

The Rise of the Khmer Empire

The Angkorian period may have begun shortly after 800 AD, when the Khmer King Jayavarman II announced the independence of Kambujadesa (Cambodia) from Java and established his capital of Hariharalaya (now known as Roluos) at the northern end of Tonlé Sap. Through a program of military campaigns, alliances, marriages and land grants, he achieved a unification of the country bordered by China to the north, Champa (now Central Vietnam) to the east, the ocean to the south and a place identified by a stone inscription as “the land of cardamoms and mangoes” to the west. In 802, Jayavarman articulated his new status by declaring himself “universal monarch” (chakravartin) and, in a move that was to be imitated by his successors and that linked him to the cult of the supreme Hindu god Shiva, taking on the epithet of “god-king” (devaraja).

- The construction of Angkor required impressive feats of hydrological engineering, hinted at here in the form of a massive retention lake.

Over the next 300 years, between 900 and 1200, the Khmer Empire produced some of the world’s most magnificent architectural masterpieces in the area known as Angkor. Most are concentrated in an area approximately 15 miles (24 km) east to west and 5 miles (8.0 km) north to south, although the Angkor Archaeological Park, which administers the area, includes sites as far away as Kbal Spean, about 30 miles (48 km) to the north. Some 72 major temples or other buildings are found within this area, and the remains of several hundred additional minor temple sites are scattered throughout the landscape beyond.

Because of the low-density and dispersed nature of the medieval Khmer settlement pattern, Angkor lacks a formal boundary, and its extent is therefore difficult to determine. However, a specific area of at least 1,000 km2 (390 sq mi) beyond the major temples is defined by a complex system of infrastructure, including roads and canals that indicate a high degree of connectivity and functional integration with the urban core. In terms of spatial extent (although not in terms of population), this makes it the largest urban agglomeration in recorded history prior to the Industrial Revolution, easily surpassing the nearest claim by the Mayan city of Tikal. At its peak, the city occupied an area greater than modern Paris, and its buildings use far more stone than all of the great Egyptian structures combined.

Construction of Angkor Wat

The principal temple of the Angkorian region, Angkor Wat, was built between 1113 and 1150 by King Suryavarman II. Suryavarman ascended to the throne after prevailing in a battle with a rival prince. An inscription says that, in the course of combat, Suryavarman leapt onto his rival’s war elephant and killed him, just as the mythical bird-man Garuda slays a serpent.

After consolidating his political position through military campaigns, diplomacy, and a firm domestic administration, Suryavarman launched into the construction of Angkor Wat as his personal temple mausoleum. Breaking with the tradition of the Khmer kings, and influenced perhaps by the concurrent rise of Vaisnavism in India, he dedicated the temple to Vishnu rather than to Siva. With walls nearly half a mile long on each side, Angkor Wat grandly portrays the Hindu cosmology, with the central towers representing Mount Meru, home of the gods; the outer walls, the mountains enclosing the world; and the moat, the oceans beyond. The traditional theme of identifying the Cambodian devaraja with the gods, and his residence with that of the celestials, is very much in evidence. The measurements themselves of the temple and its parts in relation to one another have cosmological significance.

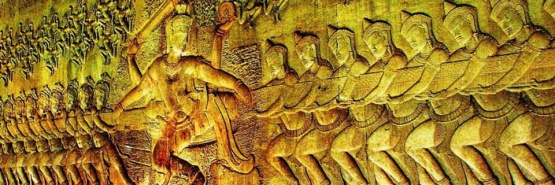

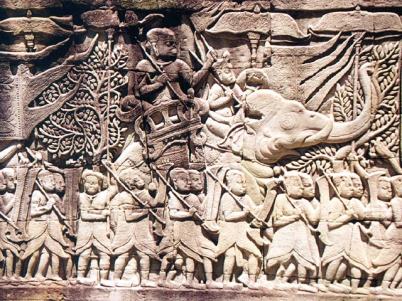

Suryavarman had the walls of the temple decorated with bas reliefs depicting not only scenes from mythology, but also from the life of his own imperial court. In one of the scenes, the king himself is portrayed as larger in size than his subjects, sitting cross-legged on an elevated throne and holding court, while a bevy of attendants make him comfortable with the aid of parasols and fans. Suryavarman portrayed himself as a “devarajas” – a “god-king” – ruler by divine right. This authority was instrumental in compelling his subjects to construct the mighty structures of Angkor.

Cosmology and Spirituality

Astronomy and Hindu cosmology are inseparably entwined at Angkor Wat. Nowhere is this more evident than in the interior colonnade, which is dedicated to a vast and glorious carved mural, a bas-relief illustrating the gods as well as scenes from the Hindu epic The Mahabharata. Along the east wall is a 45-meter (150-foot) scene illustrating the “churning of the sea of milk,” a creation myth in which the gods attempt to churn the elixir of immortality out of the milk of time. The north wall depicts the “day of the gods,” along the west wall is a great battle scene from the Mahabharata, and the south wall portrays the kingdom of Yama, the god of death. It has been suggested that the choice and arrangement of these scenes was intended to tie in with the seasons—the creation scene of the east wall is symbolic of the renewal of spring, the “day of the gods” is summer, the great battle on the west wall may represent the decline of autumn, and the portrayal of Yama might signify the dormancy, the lifeless time of winter.

The architecture of Angkor Wat also has numerous astronomical aspects beyond the basic mandala plan that is common to other Hindu temples. As many as eighteen astronomical alignments have been identified within its walls. When standing just inside the western entrance, the sun rises over the central tower on the spring (vernal) equinox; it rises over a distant temple at Prasat Kuk Bangro, 5.5 kilometers (3.4 miles) away, on the winter solstice; and on the summer solstice it rises over a prominent hill 17.5 kilometers (10.9 miles) away.

Religious Center

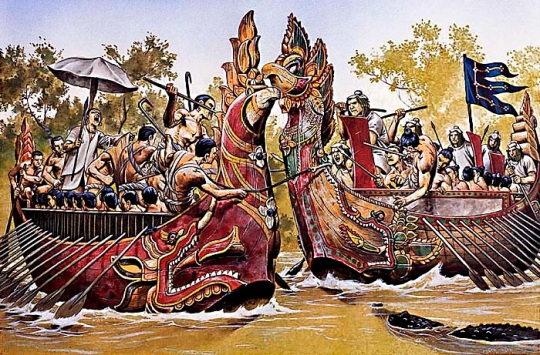

Following the death of Suryavarman around 1150 AD, the kingdom fell into a period of internal strife. Its neighbors to the east, the Cham of what is now southern Vietnam, took advantage of the situation in 1177 to launch a water-borne invasion up the Mekong River and across Tonlé Sap. The Cham forces were successful in sacking the Khmer capital of Yaśodharapura and in killing the reigning king. However, a Khmer prince who was to become King Jayavarman VII rallied his people and defeated the Cham in battles on the lake and on the land. In 1181, Jayavarman assumed the throne. He was to be the greatest of the Angkorian kings. Over the ruins of Yaśodharapura, Jayavarman constructed the walled city of Angkor Thom, as well as its geographic and spiritual center, the templeknown as the Bayon.

The Bayon is a well-known and richly decorated Khmer temple at Angkor in Cambodia. Built in the late 12th or early 13th century as the official state temple of the MahayanaBuddhist King Jayavarman VII, the Bayon stands at the centre of Jayavarman’s capital, Angkor Thom. Following Jayavarman’s death, it was modified and augmented by later Hindu and Theravada Buddhist kings in accordance with their own religious preferences.

The upper terrace is home to the famous “face towers” of the Bayon, each of which supports two, three or (most commonly) four gigantic smiling faces. There are over 200 faces, representing the Bodhisattva Lokesvara and reflect the Buddhist origins of this temple.

Daily Life in Angkor

Zhou Daguan was a Chinese diplomat from the Yuan Dynasty. He arrived at Angkor in August 1296, and remained at the court of King Indravarman III until July 1297. He was neither the first nor the last Chinese representative to visit the Khmer Empire. However, his stay is notable because he later wrote a detailed report on life in Angkor, The Customs of Cambodia. His portrayal is today one of the most important sources of understanding of historical Angkor and the Khmer Empire. Alongside descriptions of several great temples, such as the Bayon, the Baphuon, Angkor Wat, and others, the text also offers valuable information on the everyday life and the habits of the inhabitants of Angkor.

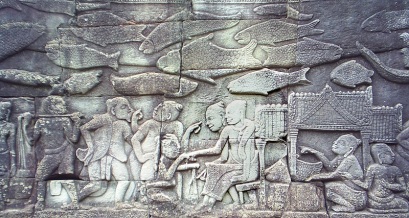

- Marketplace in ancient Angkor, bas relief in Bayon Temple. The marketplace of Angkor contains no permanent building; it was an open square where the traders sit over the ground on woven straw mat and sell their wares. There is no tables or chairs, some traders might be protected from sun with simple thatched parasol. A certain type of tax or rent cost were levied by officials for each space occupied by traders in the marketplace.

Much of what is known of the ancient Khmer society comes from the many bas-reliefs and also the first-hand Chinese accounts of Zhou Daguan, which provide information on 13th-century Cambodia and earlier. The bas-reliefs of Angkor temples, such as those in Bayon, describe everyday life of the ancient Khmer kingdom, including scenes of palace, naval battles on the river or lakes, and common scenes of the marketplace.

Economy and agriculture

The ancient Khmers were a traditional agricultural community, relying heavily on rice farming. The farmers, who formed the majority of kingdom’s population, planted rice near the banks of the lake or river, in the irrigated plains surrounding their villages, or in the hills when lowlands were flooded. The rice paddies were irrigated by a massive and complex hydraulics system, including networks of canals and barays, or giant water reservoirs. This system enabled the formation of large-scale rice farming communities surrounding Khmer cities. Sugar palm trees, fruit trees, and vegetables were grown in the orchards by the villages, providing other sources of agricultural produce such as palm sugar, palm wine, coconut, various tropical fruits, and vegetables.

Located by the massive Tonlé Sap lake, and also near numerous rivers and ponds, many Khmer people relied on fresh water fisheries for their living. Fishing gave the population their main source of protein, which was turned into prahok — dried or roasted or steamed fish paste wrapped in banana leaves. Rice was the main staple along with fish. Other source of protein included pigs, cattle, and poultry, which were kept under the farmers’ houses that were on stilts to protect them from flooding.

- Khmer women in traditional Apsara dress. An Apsara is a female spirit of the clouds and waters in Hindu and Buddhist mythology. Apsara dancers represent an important motif in the stone bas-reliefs of the Angkorian temples – Apsaras are said to be able to change their shape at will, and rule over the fortunes of gaming and gambling.

Zhou Daguan’s description on the women of Angkor suggested that in ancient Khmer society, women enjoyed significant rights and freedom, and exercised their vital economic role in a household and beyond. It is also stated that Khmer women married early, which might contribute to the high fertility rate and huge population of the kingdom:

“ | The local people who know how to trade are all women. So when a Chinese goes to this country, the first thing he must do is take in a woman, partly with a view to profiting from her trading abilities. | ”“ | The women age very quickly, no doubt because they marry and give birth when too young. When they are twenty or thirty years old, they look like Chinese women who are forty or fifty.

Society and politics

The Khmer empire was founded upon extensive networks of agricultural rice farming communities. A distinct settlement hierarchy is present in the region. Small villages clustered around regional centres, such as the one at Phimai, which in turn sent their goods to large cities like Angkor in return for other goods, such as pottery and foreign trade items from China. The king and his officials were in charge of irrigation management and water distribution, which consisted of an intricate series of hydraulics infrastructure, such as canals, moats, and massive reservoirs called barays. Society was arranged in a hierarchy reflecting the Hindu caste system, where the commoners — rice farmers and fishermen — formed the large majority of the population. The kshatriyas — royalty, nobles, warlords, soldiers, and warriors — formed a governing elite and authorities. Other social classes included brahmins (priests), traders, artisans such as carpenters and stonemasons, potters, metalworkers, goldsmiths, and textile weavers, while on the lowest social level are slaves.

The extensive irrigation projects provided rice surpluses that could support a large population. The state religion was the cult of Devaraja, elevating the Khmer kings as possessing the divine quality of living gods on earth, attributed to the incarnation of Vishnu or Shiva. In politics, this status was viewed as the divine justification of a king’s rule. The cult enabled the Khmer kings to embark on massive architectural projects, constructing majestic monuments such as Angkor Wat and Bayon to celebrate the king’s divine rule on earth.

The King was surrounded by ministers, state’s officials, nobles, royalties, palace women and servants, all protected by guards and troops. The capital city of Angkor, and the Khmer royal court is famed for its grand ceremonies, with numbers of festivals and rituals held in the city. Even during travelling, the King and his entourages created quite a spectacle, as described in Zhou Daguan’s account:

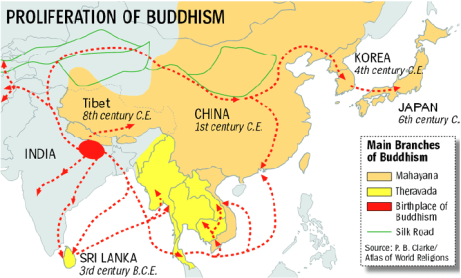

Religion

The main religion was Hinduism, followed by Buddhism in popularity. Initially the kingdom revered Hinduism as their main state religion. Vishnuand Shiva were the most revered deities, worshipped in Khmer Hindu temples. Temples such as Angkor Wat are actually known as Preah Pisnulok (Vara Vishnuloka in Sanskrit) or the realm of Vishnu, to honour the posthumous king Suryavarman II as Vishnu.

Hindu ceremonies and rituals performed by brahmins Hindu priests, usually only held among ruling elites of king’s family, nobles and the ruling class. The empire’s official religions included Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism, until Theravada Buddhism prevailed, even among the lower classes, after its introduction from Sri Lanka in the 13th century.

Culture and way of life

Zhou Daguan’s description of Khmer houses painted a simple picture:

“The dwellings of the princes and principal officials have a completely different layout and dimensions from those of the people. All the outlying buildings are covered with thatch; only the family temple and the principal apartment can be covered in tiles. The official rank of each person determines the size of the houses. ”

Houses of farmers were situated near the rice paddies on the edge of the cities. The walls of the houses were made of woven bamboo, with thatched roofs, and they were on stilts. A house was divided into three rooms by woven bamboo walls. One was the parents’ bedroom, another was the daughters’ bedroom, and the largest was the living area. Sons slept wherever they could find space. The kitchen was at the back or in a separate room. Nobles and kings lived in the palace and much larger houses in the city. They were made of the same materials as the farmers’ houses, but the roofs were wooden shingles and had elaborate designs as well as more rooms.

The common people wore a sampot where the front end was drawn between the legs and secured at the back by a belt. Nobles and kings wore finer and richer fabrics. Women wore a strip of cloth to cover the chest, while noble women had a lengthened one that went over the shoulder. Men and women wore a Krama. Along with depictions of battle and the military conquests of kings, the bas-reliefs of Bayon depict the mundane everyday life of common Khmer people, including scenes of the marketplace, fishermen, butchers, people playing a chess-like game, and gambling during cockfighting.

Decline

By the 14th century, the Khmer empire suffered an arduous, long and steady decline. Historians has been trying to figure out the real cause for the decline of once great empire. Numbers of possible factors has been proposed; from the religious conversion from Vishnuite-Shivaite Hinduism faith to Theravada Buddhism that might effects social and political systems, incessant internal power struggle among Khmer princes, vassal revolt, foreign invasion, to plague and ecological breakdown.

For social and religious reasons, many aspects contributed to the decline of the Khmer empire. The relationship between the ruler and their elites was unstable — among the 27 Angkorian rulers, eleven lacked legitimate claim to the power, and civil wars were frequent. The Khmer empire focused more on domestic economy and did not take advantage of the international maritime network. In addition, the input of Buddhist ideas conflicted and disturbed the state order built under predominately Hindu religion.

Epidemic

There is evidence that the “Black Death” had affected the situation described above, as the plague first appeared in China around 1330 and reached Europe around 1345. Most seaports along the line of travel from China to Europe felt the impact of the disease, which had a severe impact on life throughout South East Asia.

Conversion of faith

The last Sanskrit inscription is dated 1327, and describes the succession of King Indrajayavarman by Jayavarmadiparamesvara.Historians suspect a connection with the kings’ adoption of Theravada Buddhism: they were therefore no longer considered “devarajas” – the “god-king” – and there was no need to erect huge temples to them, or rather to the gods under whose protection they stood. The retreat from the concept of the devaraja may also have led to a loss of royal authority and thereby to a lack of workers. The water-management apparatus also degenerated, meaning that harvests were reduced by floods or drought. While previously three rice harvests per year were possible, the declining harvests further weakened the empire.

The last Sanskrit inscription is dated 1327, and describes the succession of King Indrajayavarman by Jayavarmadiparamesvara.Historians suspect a connection with the kings’ adoption of Theravada Buddhism: they were therefore no longer considered “devarajas” – the “god-king” – and there was no need to erect huge temples to them, or rather to the gods under whose protection they stood. The retreat from the concept of the devaraja may also have led to a loss of royal authority and thereby to a lack of workers. The water-management apparatus also degenerated, meaning that harvests were reduced by floods or drought. While previously three rice harvests per year were possible, the declining harvests further weakened the empire.

Foreign pressure

The western neighbor of the Khmer, the first Thai kingdom of Sukhothai, after repelling Angkorian hegemony, was conquered by another stronger Thai kingdom in the lower Chao Phraya Basin, Ayutthaya, in 1350. From the fourteenth century, Ayutthaya became Angkor’s rival. Angkor was besieged by the Ayutthayan king Uthong in 1352, and following its capture the next year, the Khmer monarch was replaced with successive Siamese princes. Then in 1357, the Khmer king Suryavamsa Rajadhiraja regained the throne. In 1393, the Ayutthayan king Ramesuan besieged Angkor again, capturing it the next year. Ramesuan’s son ruled Khmer a short time before being assassinated. Finally, in 1431, the Khmer king Ponhea Yat abandoned Angkor as indefensible, and moved to the Phnom Penh area.

The new center of the Khmer kingdom was in the southwest, at Oudong in the region of today’s Phnom Penh. However, there are indications that Angkor was not completely abandoned. One line of Khmer kings could have remained there, while a second moved to Phnom Penh to establish a parallel kingdom. The final fall of Angkor would then be due to the transfer of economic — and therewith political — significance, as Phnom Penh became an important trade center on the Mekong RIver. Besides, the severe droughts and ensuing floods were considered as the one of the contributing factors to its fall. The empire focused more on regional trade after the first drought. Overall, climate change, costly construction projects, and conflicts over power between the royal family sealed the end of the Khmer empire.

Ecological breakdown

Ecological failure and infrastructural breakdown is a new alternative theory regarding the end of the Khmer Empire. Scientists working on the Greater Angkor Project believe that the Khmers had an elaborate system of reservoirs and canals used for trade, travel, and irrigation. The canals were also used for harvesting rice. As the population grew there was more strain on the water system. During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, there were also severe climatic changes impacting the water management system. Periods of drought led to decreases in agricultural productivity, and violent floods due to monsoons damaged the infrastructure during this vulnerable time.To adapt to the growing population, trees were cut down from the Kulen hills and cleared out for more rice fields. That created additional rain runoff carrying sediment to the canal network.

Ecological failure and infrastructural breakdown is a new alternative theory regarding the end of the Khmer Empire. Scientists working on the Greater Angkor Project believe that the Khmers had an elaborate system of reservoirs and canals used for trade, travel, and irrigation. The canals were also used for harvesting rice. As the population grew there was more strain on the water system. During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, there were also severe climatic changes impacting the water management system. Periods of drought led to decreases in agricultural productivity, and violent floods due to monsoons damaged the infrastructure during this vulnerable time.To adapt to the growing population, trees were cut down from the Kulen hills and cleared out for more rice fields. That created additional rain runoff carrying sediment to the canal network.

The Bottom Line

- Why isn’t the Khmer Empire included in your world history textbook? Should it be?

- Research another of the temples within the Angkor complex and create a poster or infographic that introduces this structure to a wider audience.

- As you have read, the ruins of Angkor teach us a great deal of what we know about the Khmer Empire. A thousand years from now, what ruins and artifacts from your civilization will be left behind? What will they tell future archaeologists about the values, achievements, and practices of your society?

- What factors contributed to the fall of Angkor? What lessons from this example might be applied to modern cities facing economic and environmental change?

You can actually visit parts of the world featured in the lesson:

Scenes from Cambodia, 2014 – supplementary photos to enhance a sense of place.

this is a very helpful site. I found what I was looking for easily and had no trouble using it.

LikeLike

This is great stuff. The dearth of good materials on the East in a Western classroom is something I’ve been lamenting. Really glad you’re bridging the gap.

LikeLike